Intellectual property (IP) is a product of the human mind that the law protects from unauthorized use by others. The concept of IP is that certain products of human intellect should be afforded the same protective rights that apply to physical property. Most developed countries have legal measures in place to protect at least four types of IP: patents, copyrights, trademarks, and trade secrets.

A patent is a property right granted by a government to an inventor. This grant provides the

inventor exclusive rights to the patented invention for a designated period of time

in exchange for a comprehensive disclosure of the invention. In the United States,

the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) handles patent applications and grants approvals. In order to receive a patent, an invention must be considered novel, useful, and non-obvious and be either a process,

machine, method of manufacture, or composition of matter.

A copyright is a legal protection for creative works of the mind. Under U.S. copyright law, this protection is for "original works of authorship." These works include writings, music, visual art, choreography, and software and such works must be tangibly expressed. Copyrights prevent others from reproducing, distributing, publicly performing, displaying, and preparing derivative works without express permission of the copyright owner. Copyrights are afforded protection for a maximum period of the life of the author plus 70 years (exceptions apply to works for hire and anonymous works).

A trademark protects words, names, symbols, sounds, or colors that are used to distinguish goods

and services from those manufactured or sold by others. Trademarks, unlike patents,

can be renewed forever as long as they are being used in commerce.

A trade secret is a process or practice that is not public information and which provides an economic benefit or advantage to the company or holder of the trade secret. Trade secrets must be actively protected by the company and are typically the result of a company's research and development. Examples of trade secrets include designs, patterns, recipes, formulas, or proprietary processes.

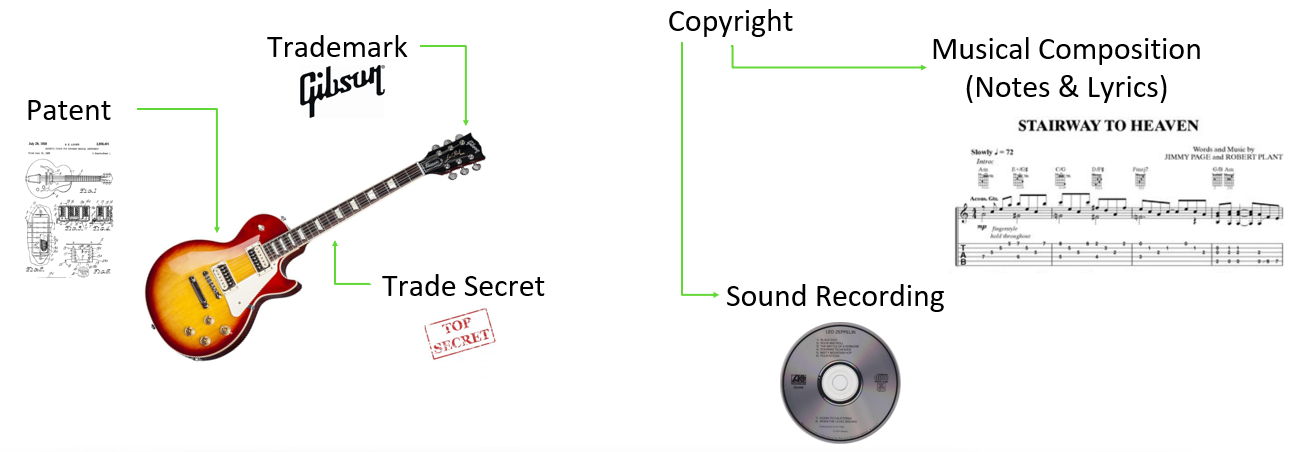

Here’s a real-world example that showcases all four types of intellectual property (IP) along with an example of IP litigation:

The Gibson Guitar Corporation manufactures and sells guitars and other musical instruments. Their guitars are constructed using certain company trade secrets, including manufacturing techniques for producing solid-body electric guitars. In the 1950's, Gibson invented a noise-cancelling guitar pickup called a "humbucker" and a patent was awarded for this technology (USP 2,896,491). Gibson soon began to sell some of its electric guitars with the patented humbucker. One such guitar is known as the Gibson Les Paul and has become one of the most famous guitars in the world for its distinctive tone. The Gibson trademark is affixed to the headstock of the Gibson Les Paul guitar so consumers can recognize the instrument as originating from Gibson.

The musician Jimmy Page played a Gibson guitar. He and his bandmate, Robert Plant, wrote a song called "Stairway to Heaven" for their rock band Led Zeppelin. Many regard this song as the most iconic rock song of all time. The musical composition (notes and lyrics) is protected under copyright. The sound recording produced by the band and their record label is also protected under copyright.

In May 2014, two musicians of the rock band Spirit sued Led Zeppelin for IP infringement (copyright infringement) of their song "Taurus," which was released two years prior to "Stairway to Heaven." Past earnings of the Led Zeppelin song were estimated at over $550 million. After a trial and several appeals, the Ninth Circuit ruled on March 9, 2020 that there was no copyright infringement. Later that year, Spirit petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the case. The petition was denied, leaving in place the Ninth Circuit's ruling in favor of Led Zeppelin.

What is a U.S. Patent?

A patent is a form of intellectual property granted to an inventor under the U.S. Constitution and federal law. It acts as a government-sanctioned monopoly on a new invention for a limited period of time (20 years from the date of filing) in exchange for the disclosure of the invention to the public. The patent system is designed to encourage disclosure of unique and useful inventions to the public.

What Rights Does a U.S. Patent Provide?

A patent does not grant the patent owner any right to make their own invention. Rather, a patent gives the patent owner the right to exclude others from making, using, or selling the invention throughout the United States, or importing the invention into the United States for the duration of the patent. The patent holder's right to make their own invention is dependent upon the intellectual property rights of others.

What Cannot be Patented?

Laws of nature, physical phenomena, abstract ideas, algorithms, and scientific theories or principles may not be patented.

What Can Be Patented?

Most anything made by an inventor, along with the processes for making an invention, can be patented. There are three types of patents:

What Are the Requirements for Patentability?

An invention is “novel” if it is different from other similar inventions (whether or not previously patented). It must not have been sold, offered for sale, in public use, or otherwise available to the public prior to the filing date of the patent application.

An invention is “non-obvious” if the invention is sufficiently new and inventive (e.g., would not be obvious to someone within the relevant industry or with the relevant skills based on the information and inventions that have come before it). The idea behind requiring non-obviousness is to avoid granting patents for the normal stages of development of a concept or idea that are not true inventions in themselves.

An invention is “useful” if it has some identifiable benefit and is capable of use. This protects against patenting hypothetical devices and ideas.

How is Patent Protection Obtained?

Unlike copyright, patent protection does not automatically exist upon creation. Instead, an inventor must apply for a patent with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

Preparing and filing a patent application is time consuming and costly. For inventors that are unsure of the commercial viability of the invention or are in a hurry to get a patent application on file, the USPTO provides a provisional patent application process. A provisional patent application is an abbreviated application that allows inventors to preserve an earlier filing date and gives the inventor 12 months in which to file a patent application. Provisional patent applications will never themselves mature into an issued patent, but the early filing date can be important to secure patent rights given that patents within the United States are awarded on a “first to file” basis, rather than a “first to invent” basis. Provisional patent applications can also be helpful to preserve rights that may otherwise be lost if the inventor makes certain public disclosures or offers for sale of the invention more than 12 months before the patent application is filed.

An inventor who wishes to obtain patent protection in other countries must apply for a patent in each of the other countries or in regional patent offices, in cases where a patent may be obtained for multiple countries at once by operation of treaty or otherwise.

Utility and plant patents last for 20 years from the application date whereas design patents last for 14 years. Failure to file required documents or pay specified fees may result in the loss of a patent. An invention becomes public upon expiration of the patent and can then be made, used, sold, offered for sale, or imported by anyone.

What is Patent Infringement?

Copyright law protects original works of authorship and provides the creator with certain exclusive rights, subject to some exceptions and limitations. The following "Copyright Decision Tree" is designed to help faculty make informed decisions about whether using another's work is legal under copyright law. If an exemption is required, refer to the applicable exemption flowchart to determine whether such exemption is available. Please contact the Fulton Library or our Office with any questions.

What is Copyright?

Copyright is a form of protection afforded under the U.S. Constitution and federal law to “original works of authorship” that are fixed in a tangible form of expression (e.g., written down, audio recorded, videotaped, etc.). These works include literary, dramatic, musical, artistic, pictorial, and other intellectual works. Copyright essentially covers any work that is creative and recorded in some physical medium, regardless of whether the work is published or unpublished.

What Rights Does a Copyright Provide?

What Can Be Copyrighted?

What Works Are Not Protected Under Copyright?

How is Copyright Protection Obtained?

Under U.S. copyright law, a copyrightable work is protected from the moment the work is created and fixed in a tangible form. No registration or publication is required. However, there are important benefits to registering a copyright. These include giving others notice of the copyright and making it easier to license the work, collect royalties, and enforce ownership rights. Copyright registration is also required to bring a lawsuit for copyright infringement and obtain certain kinds of damages or fees in court. A copyright typically lasts for the life of the author/creator plus an additional 70 years for anything created after 1978. For an anonymous work or work for hire, the copyright lasts for 95 years from the date of first publication or 120 years from the date of creation, whichever expires first. For works published before 1978, the term may vary depending on the specific circumstances.

Copyright law only grants the owner of a creative work certain exclusive rights for activities within the United States. A creator who wishes to obtain copyright protection in other countries must file for protection and/or meet the requirements for such protection in any other countries in which protection is sought.

What is Copyright Infringement?

Exceptions to Copyright Holder’s Exclusive Rights

The rights provided to copyright holders under the Copyright Act are exclusive, meaning they give the holder the exclusive right to make, reproduce, and distribute copies of the work, prepare derivative works, as well as perform or display the work publicly. However, there are some exceptions under copyright law that allow works to be used without violating these exclusive rights. These exceptions include, among others:

Additional exceptions not discussed here include the statutory exception for libraries and archives as well as where necessary to ensure access for those with disabilities. Many works have also been dedicated to the “public domain,” meaning that they may be used without violating a copyright holder’s rights. Please contact the Fulton Library or our Office with any questions.

Face-to-Face Teaching Exception

The Copyright Act includes a face-to-face teaching exemption, which allows instructors to perform or display copyrighted works (e.g., films, writings, etc.) in class without violating the copyright holder’s rights. The exemption does not include the right to make or distribute copies of, or make derivative works based on, the copyrighted works or the right to use the works outside of the classroom setting.

To qualify for the face-to-face teaching exemption, the following must apply:

If these requirements are met, then copyrighted works may be displayed or performed in the classroom. This means, for example, that students and instructors can watch movies, perform scenes from a play, or display photographs of artistic works within the classroom for educational purposes without first obtaining permission or a license. This exemption does not apply to other uses of the copyrighted works (e.g., copying or distribution) or to uses outside of the classroom setting. In such cases, other exceptions, such as the TEACH Act or Fair Use, may apply depending on the specific facts and circumstances.

Distance Learning (The TEACH Act) Exception

The Technology, Education, and Copyright Harmonization (“TEACH”) Act of 2002 was enacted as a way to support online education and balance the needs of distance learning with the rights of copyright holders. The TEACH Act made copyright laws and requirements for distance learning similar to those for face-to-face teaching, though there are still some significant differences. The TEACH Act permits educators and students to transmit performances and displays of copyrighted works as part of a distance learning course if the requirements of the TEACH Act are met. Any distance learning activities outside the protections of the TEACH Act need to have permission or qualify for another exemption (e.g., public domain, fair use, etc.).

The TEACH Act requires that academic institutions meet a variety of requirements in order for its exemptions to apply. These requirements ensure that the copyrighted works are being used in a permitted manner and that the academic institution has sufficient policies and practices in place for copyright compliance and education. These requirements include, among others:

Materials permitted to be used under the TEACH Act include:

Fair Use Exception

Public Domain

A public domain work is a creative work that is not protected by copyright and that may be used without violating copyright law. Individuals are able to use such works without obtaining permission or a license to use the work.

Works within the public domain:

There are many sources of public domain work. Below is a list of some potential sources, though users should confirm that a work is dedicated to the public domain before using.

Third Party Links:

Music on Campus (Outside the Classroom)

Music is protected under copyright law and is one of the most difficult types of creative works to license. This is due to the multiple layers of rights for each song. First, under copyright law there are two different copyrights that must be considered, the copyright in the musical composition and the copyright in the sound recording. Second, the owner of each copyright then holds exclusive rights to reproduce, distribute, publicly perform, publicly display, and prepare derivatives of the work. These exclusive rights are subject to certain exceptions and limitations. Please refer to the UVU Copyright Decision Tree as you make an informed decision about whether using another's work is legal under copyright law. If a music license is required, the following two tables will identify the party that owns or controls the rights. Please contact our Office with any questions.

License for Performance Rights

The performance or playing of copyrighted music on campus typically requires that the University have licenses with Performing Rights Organizations (“PROs”) such as ASCAP, BMI, SESAC, SoundExchange, or GMR. These PROs distribute money derived from the licensing fees to the songwriters, musicians, and publishers of the copyrighted works. If a license exists between a particular PRO and the University, any of that PRO’s collection of songs can be played on campus.

Other Music Licenses

Depending on the nature of the activity, a basic PRO performance rights license may need to be supplemented with other licenses. For instance, the University may need to add a license for grand rights, which grants permission to perform music in staged works, such as plays, musicals, or operas. These rights can be negotiated for certain works by contacting organizations such as the Tams-Witmark Music Library, Inc., the Rodgers & Hammerstein Organization, Music Theatre International, and Samuel French, Inc. Otherwise, it may be necessary to reach out to the individual copyright owners, publishers, or writers to negotiate the fees for the right to perform their works on stage.

If streaming copyrighted music via certain digital transmissions, including satellite radio, non-interactive internet radio, cable TV music channels, and similar platforms, the University will need a streaming license. SoundExchange usually is responsible for collecting and distributing these royalties on behalf of recording artists, master rights owners, and independent artists.

If incorporating copyrighted music into a visual or multimedia product, the University may need to acquire a synchronization license. This scenario most often arises when creating commercials, marketing materials, or YouTube videos. This type of license is usually obtained from publishing companies directly. In a limited number of cases, these licenses may be available from Stockmusic.net, Getty Images, GreenLight Music, and The Music Bed Company.

If reproducing and distributing copyrighted songs on CDs, records, tapes, ringtones, permanent digital downloads, or interactive streams, the University will need a mechanical license. These usually are acquired by contacting the Harry Fox Agency, which is owned by SESAC.

Exceptions to Music License Requirement

There are four main exceptions when a music license is not required:

What is a Trademark?

What Rights Does a Trademark Provide?

How is Trademark Protection Obtained?

Trademark rights come from actual use. Unlike patents and copyrights, trademarks do not expire after a set term of years and therefore, a trademark can last forever so long as you continue to use the mark in commerce to indicate the source of goods and services. Trademark registration can also last forever so long as you file specific documents and pay fees at regular intervals.

Registration is not mandatory as you can establish “common law” rights in a mark based solely on use of the mark in commerce without a registration. However, federal registration of a trademark with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has several advantages, including: providing public notice of the registrant’s claim of ownership of the mark, a legal presumption of ownership nationwide, listing in the USPTO’s online databases, the ability to record the U.S. registration with U.S. Customs and Border Protection to prevent importation of infringing foreign goods, the ability to bring an action concerning the mark in federal court, the use of U.S. registration as a basis to obtain registration in foreign countries, and the exclusive right to use the mark on or in connection with the goods and services set forth in the registration.

If a mark is registered with the USPTO, the ® symbol should be used after the mark. If not yet registered, the ™ symbol for goods or ℠ symbol for services may be used to denote a “common law” trademark or service mark.

Are All Marks Registrable With the USPTO or Legally Protectable?

Use and Protection of UVU Trademarks