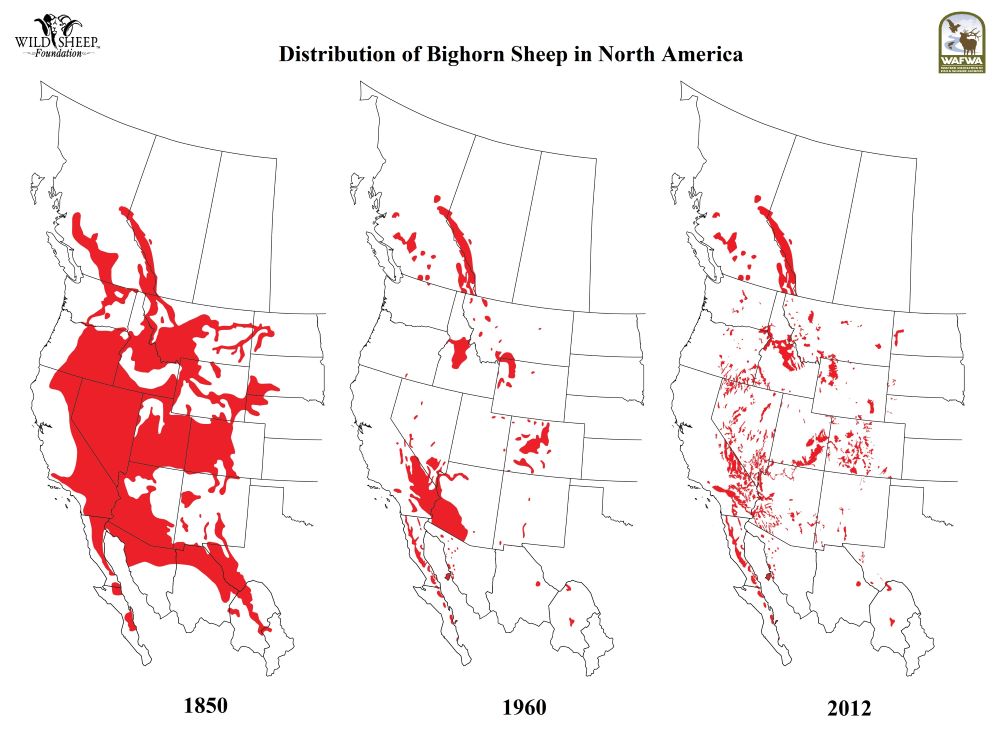

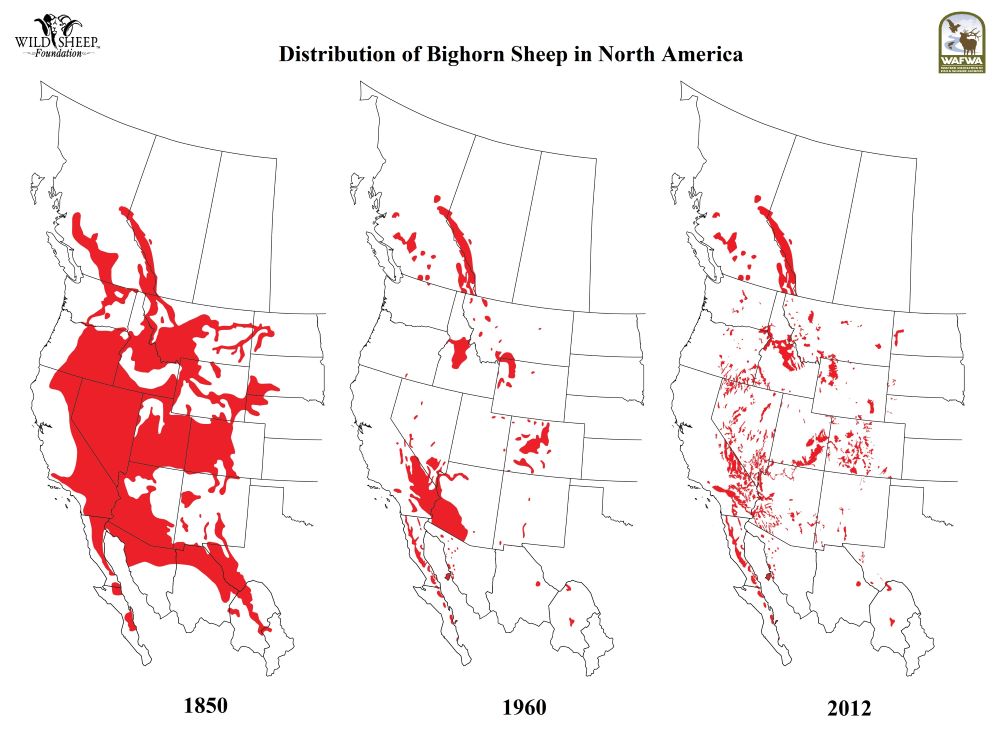

Bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) are an iconic North American mammal that inhabit rugged mountain and desert ecosystems

from northern Mexico to southern Canada. Bighorns were well-established throughout

these habitats until impacts from increased human settlement began to take a toll

on the species. Widespread population declines and extirpations (local extinction)

occurred from the late 1800s to mid-1900s mainly due to competition and disease transmission

from domestic livestock, habitat loss, and unregulated hunting (Figure 1). Although

there is considerable uncertainty around historic bighorn sheep population estimates,

Father Escalante observed the great abundance of bighorns during the famous Dominguez-Escalante

Expedition of 1776: “through here wild sheep live in such abundance that their tracks

are like those of great herds of domestic sheep” (UDWR 2012).

Watch the short Wild & Wool documentary

Bighorn populations disappeared all over the western U.S., and by the 1940s desert

bighorns (O. c. nelsoni) were extirpated from Capitol Reef National Park (Sloan 2007); by the 1960s, desert

bighorns were barely holding on in small isolated groups on the Colorado Plateau,

such as in Canyonlands National Park. The species was disappearing, and extensive

conservation and management action was needed.

Starting in the 1960s, wildlife managers began an ambitious reintroduction effort

in Utah, capturing some sheep from remaining populations and relocating them to historic

habitats (Singer et al. 2000, Wild Sheep Working Group 2015). In most cases, it worked,

and populations slowly recovered. Within Utah alone, over 1,000 desert bighorns and

1,200 Rocky Mountain bighorns (O. c. canadensis) were transplanted over the past 40 – 50 years (UDWR 2012). This management tool

was used throughout the West, and bighorn relocations have occurred in 15 U.S. states

as well as within Canada, since the first relocation in 1922 (Wild Sheep Working Group

2015). Relocation is still used as a management tool today. The sheep of Capitol Reef

National Park, and in many areas in Utah and the West, are therefore native transplants

that have reestablished parts of their historic range.

Although reintroductions in Utah and the West have been largely successful, particularly

for desert bighorns, bighorn sheep still face many threats, especially disease transmission

from domestic livestock (the primary threat – watch the short Wild & Wool documentary), habitat loss from development, and more recently disturbance from recreation

(Papouchis et al. 2001, Sproat et al. 2020). The latter is particularly relevant in

Capitol Reef National Park given the dramatic increase in park visitation: in 2019

approximately 1,226,519 people visited Capitol Reef National Park, increasing 50%

from 2014 (786,514 visitors) and more than double 2008 visitation (604,811; NPS Stats).

There are more people on trails, more people in the backcountry, and the ‘busy season’

is longer, which all increase the likelihood of bighorns being disturbed by people.

Seasonal closures of critical habitat, such as during lambing season, can help mitigate

the effects of increased visitation, but closures need to be justified by current

data and should be targeted to maximize benefits to bighorn sheep while minimizing

impacts on park visitors. Continued research and management are therefore needed to

ensure persistence of these populations.

Within this complicated and fascinating context, Capitol Reef Field Station (CRFS),

UVU, and NPS scientists are studying desert bighorns in Capitol Reef National Park

using motion-sensor cameras and DNA extracted from bighorn scat. We are using these

non-invasive techniques to better understand desert bighorn distribution, abundance,

habitat use, and genetic population connectivity in order to improve management and

help ensure that this iconic species persists in the wild (Figures 2-6).

Figure 1. Change in bighorn sheep distribution over time - (Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies and the Wild Sheep Foundation)

Figure 2. Motion-sensor wildlife cameras for CRFS/UVU/NPS research on desert bighorn

sheep in Capitol Reef National Park - Photo: J. Ceradini

Figure 3. Wildlife camera mounted to tree in the Kayenta rock layer far above Capitol

Gorge in Capitol Reef National Park - Photo: J. Ceradini

Figure 4. Desert bighorn sheep scat on a Kayenta bench far above Grand Wash (Fern's Nipple Navajo sandstone dome in the distance), Capitol Reef National Park.

Scat surveys were conducted at each site and DNA was extracted for genetic analysis

in a UVU genetics lab. - Photo: J. Ceradini

Figure 5. One of the many beautiful and challenging backcountry field days on the

bighorn project, Capitol Reef National Park - Photo: J. Ceradini

Figure 6. Desert bighorn ewe (female) and lamb, Capitol Reef National Park - Photo: wildlife camera from CRFS/UVU/NPS bighorn research