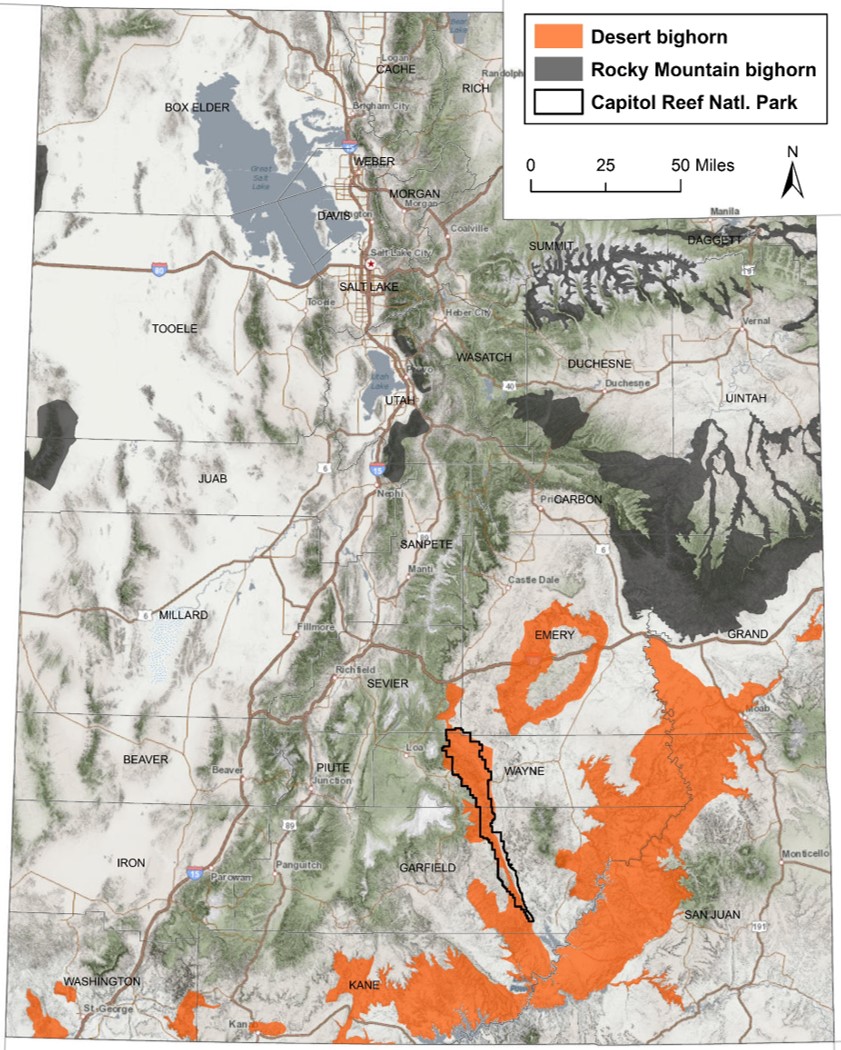

Bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) are an impressive large mammal native to North America that inhabit rugged and steep terrain in mountain and desert ecosystems from northern Mexico to southern Canada (Valdez and Krausman 1999, UDWR 2012). There are several bighorn sheep subspecies, but the two primary subspecies in Utah (Figure 4) are the Desert bighorn (Ovis canadensis nelsoni) and Rocky Mountain bighorn (Ovis canadensis canadensis). As their names suggests, the subspecies are adapted to different ecosystems. Desert bighorns inhabit lower, drier, and hotter canyon country, such as Capitol Reef National Park, and Rocky Mountain bighorns inhabit the higher, wetter, and cooler mountains, like the Wasatch Mountains.

Figure 4. Distribution map of desert and Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep subspecies in Utah.

Map produced by J. Ceradini with Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Utah AGRC, and NPS data.

Figure 1. Desert bighorn sheep ram (male), Pleasant Creek, Capitol Reef National Park - Photo: J. Ceradini

Figure 2. Desert bighorn sheep ram (male), Capitol Reef National Park - Photo: Nielson/NPS

Figure 3. Desert bighorn sheep ewe (female) and lamb, Capitol Reef National Park - Photo: wildlife camera from CRFS/UVU/NPS research

Obtaining resources: like all animals, appropriate food and water are essential resources for desert bighorn sheep.

Evading predators: bighorn sheep are social prey animals that are hunted by a variety of predators, primarily mountain lions (Puma concolor). They have evolved strategies to reduce predation risk, such as by selecting habitats that provide refuge from predation and where predators can be more easily detected by the herd.

To summarize the foraging and predator evasion strategy of both desert and Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep:

Bighorn sheep tend to forage diurnally (during the daytime) in dispersed groups within open habitat that is close to escape terrain. This habitat selection strategy allows them to obtain food in an area where they can, as a group, effectively detect predators and quickly access escape terrain to evade predators when needed.

References: Valdez and Krausman 1999, UDWR 2012, Robinson et al. 2020.

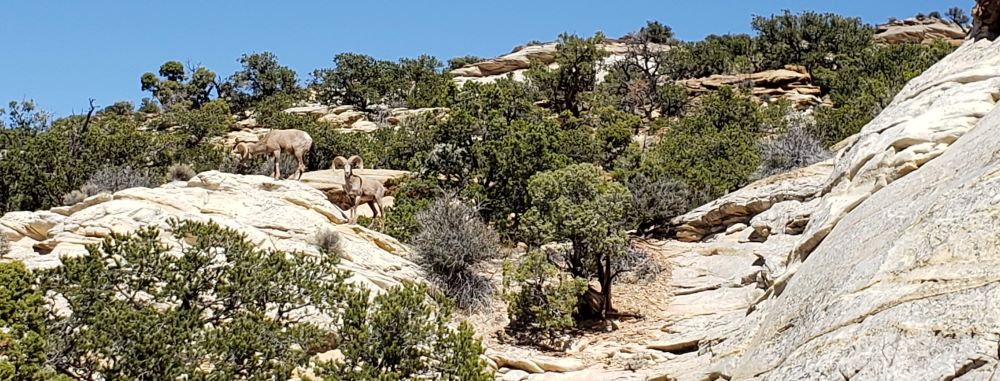

Figure 5. Habitat scale 1: two mature desert bighorn rams (males) on a mesa within the Kayenta rock layer that has interspersed outcrops of Navajo sandstone and moderate density of pinyon and juniper trees, Capitol Reef National Park. Photo also illustrates a benefit of having at least one friend: one sheep forages while the other watches the photographer. Social prey animals, like sheep and deer, experience a tradeoff between foraging and being vigilant for predators. Sheep and deer often forage in dispersed groups to take advantage of "group awareness" of predators, giving each individual more time to forage than if they were alone. - Photo: J. Ceradini

Figure 6. Habitat scale 2: two desert bighorn rams (males) in the upper-center of photo. This scale shows more of the rock outcrops, open space between pinyons and junipers, and overall complicated nature of the terrain, Capitol Reef National Park - Photo: J. Ceradini

Figure 7. Habitat scale 3: no sheep in this picture, sorry. The sheep in Figures 5 and 6 were near the white circle. Broad scale habitat view showing the Kayenta pinyon-juniper mesa transitioning to large Navajo sandstone domes to the east (right), Capitol Reef National Park. This photo illustrates the broader context of the habitat in Figures 5 and 6, and also how wildlife habitat is understood at multiple spatial scales. For example, there are at least three aspects of this location that reduce predation risk: 1) at the local scale, the sheep have small rock outcrops and complicated terrain to stay hidden within, 2) at the broader scale, the Kayenta rock layer sits on top of the large Wingate sandstone cliffs (seen running north toward Thousand Lake Mountain in the background), which limit access to the Kayenta from below to only a few "breaks" in the Wingate, and 3) also at the broader scale, the rugged and steep Navajo sandstone domes serve as escape terrain for bighorn sheep, providing a partial refuge from predators - Photo: J. Ceradini

Figure 8. Broad scale view of the Fremont River/Highway 24 corridor that is dominated by the Navajo sandstone layer, Capitol Reef National Park. This area is used extensively by desert bighorn sheep because, 1) the rugged and steep Navajo sandstone provides excellent escape terrain but is still interspersed with vegetation for foraging, and 2) the Fremont River provides a year-round water source that is essential to many desert wildlife species including bighorn sheep - Photo: J. Ceradini

Figure 9. Another view of the Fremont River/Highway 24 corridor showing the juxtaposition of the Fremont River, with its flat and relatively lush riparian zone, and the rugged, dry, and sparsely vegetated Navajo sandstone above. Desert bighorn sheep frequently move between these two contrasting and essential habitat types, which also illustrates the importance of connectivity between different habitat types for wildlife - Photo: J. Ceradini

How do they do it? Strategies for coping with desert heat and drought can be divided into three categories:

physiological, morphological, and behavioral.

(Many of these adaptations are also common in other desert-adapted ungulates, such as donkeys, goats, camels, and gazelles).

References: Valdez and Krausman 1999, Cain et al. 2005, Cain et al. 2006, Reid 2006.

Figure 10. Desert bighorn ewe (female) kneeling for an icy drink in Pleasant Creek, Capitol Reef National Park, while other sheep graze in the shrublands above the creek - Photo: J. Ceradini

Figure 11. Mixed group of desert bighorns easily navigating a steep loose creek bank to grab an icy drink in Pleasant Creek, Capitol Reef National Park - Video: J. Ceradini