Lichens & Adaptations

Thus, one of lichens’ defining characteristics is their adaptability, testified to by their success and the breadth of their distribution across the planet, accounting for 8 percent of life on Earth’s land surface (Williams, 2020). Heimbuch (2020) notes it is said of lichen that they “grow in the leftover spots of the natural world that are too harsh or limited for most organisms. They even have defenses with which to battle against threat and competition (Heimbuch, 2020; Yong, 2012). Curiously, lichens’ place in soil formation almost seems counterproductive to its adaptability. In other words, lichens’ role as a pioneering or “colonizing” species helps break down rock and begin the process of “fixing” nitrogen in the soil to make airborne nitrogen usable by the lichen as well as plant and soil life in the future, perhaps creating adverse conditions and competition for itself.

Even so, the process is central to desert soils and “biological crusts.” This is to say that lichens in a desert ecology are typically connected to and working with the biological crusts. In a High Country News article titled, “Getting under the desert’s skin,” Nijhuis (2004) quotes scientist Jayne Belnap who says, “This [a landscape such as we see in Capitol Reef] is not a rocky landscape, this is a cyanobacteria landscape—it’s covered with life,” she says. “These landlocked colonies of blue-green algae,” she says,” are the ‘skin’ of desert soils and many other surfaces of the planet.”

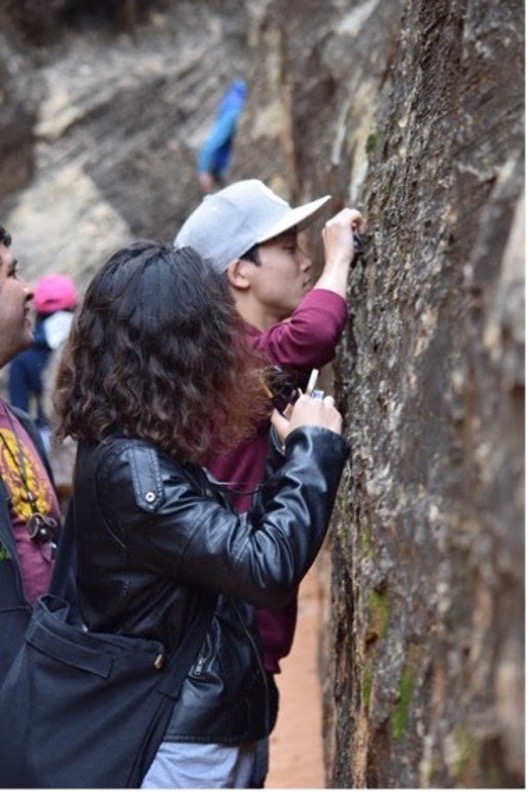

During your time at Capitol Reef, your trip facilitators will no doubt give you more guidance on “Don’t Bust the Crust!” This may be even more important when considering lichen. Further on, when discussing the research on cyanobacteria recovering in disturbed areas, Nijhuis (2004) notes that the researchers found that “mosses and lichens—the most effective nitrogen fixers—do not return to full strength for 250 years or even more.” Clearly even after 150 years of documenting one of the most intensely studied symbiotic relationship in biology, lichens still retain mysteries and lessons to teach us.