Our culture loves to produce fantasies of dystopia, such as 1984, Brave New World, and Fahrenheit 451. To decide whether any of our fabulously bleak dystopias have already come to pass, it is an important first step to define dystopia. Dystopia is a slippery thing. It is a type of state, or maybe a place, but also a literary genre typified by that kind of state/place. If a work fails to match every point of the definitions here, that does not necessarily preclude it from being dystopia. Although, as an ideal term, there is no such thing as a true dystopia. The next goal of this paper is nevertheless to define an ideal dystopia, which I refer to as “the machine-state”. The machine-state will then be used as a measuring stick to analyze what is dystopic in our own world, while drawing on controversial, yet often insightful thinkers such as Karl Marx and Ted Kaczynski. I want to do this because I believe that we may already be in a dystopia, but perhaps that is not so bleak a prospect as it sounds.

Our culture loves to produce fantasies of dystopia, such as 1984, Brave New World, and Fahrenheit 451. To decide whether any of our fabulously bleak dystopias have already come to pass, it is an important first step to define dystopia. Dystopia is a slippery thing. It is a type of state, or maybe a place, but also a literary genre typified by that kind of state/place. If a work fails to match every point of the definitions here, that does not necessarily preclude it from being dystopia. Although, as an ideal term, there is no such thing as a true dystopia. The next goal of this paper is nevertheless to define an ideal dystopia, which I refer to as “the machine-state”. The machine-state will then be used as a measuring stick to analyze what is dystopic in our own world, while drawing on controversial, yet often insightful thinkers such as Karl Marx and Ted Kaczynski. I want to do this because I believe that we may already be in a dystopia, but perhaps that is not so bleak a prospect as it sounds.

I will be using the term the “machine-state” to describe the perfect dystopia. This conception is mainly informed by the seminal dystopian works 1984 by George Orwell, Brave New World by Aldous Huxley, Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury, The Machine Stops by E.M. Forester, and the film Brazil directed by Terry Gilliam, as well as many others. These works will be referenced throughout this paper in passing. Intimate knowledge of their details is not required. What does need to be known is that these works are unified by themes of totalitarian or authori tarian governments, technological dehumanization, alienation, individual resentment, and futility.

Dystopia as Machine-State

First, what do we mean when we use the term “dystopia” in general? Merriam-Webster’s first definition is “an imagined world or society in which people lead wretched, dehumanized, fearful lives.”1That seems apt, if a little simple. Merriam-Webster’s second definition of “Anti-utopia” helps contextualize it a little as being in opposition to a utopia.2 A barren nuclear wasteland may be an imagined world or society in which people lead wretched, dehumanized, fearful lives, but it is not the opposite of a utopia the same way that the kind of twisted society in the following paragraphs would be.

Expanding on the above dictionary definitions we might say, based on general trends of dystopic literature, that dystopian governments are typically enabled in their oppression by new technology, power structures, and exaggerated ideological and cultural forces . They often involve elements of post-apocalypse or global catastrophes of various kinds. The characters of dystopic fiction are often people who have resigned themselves to their place in their oppressive society to some extent but may still harbor some resentment. The setting may be so hopeless that those characters’ journeys were doomed from the start, creating feelings of despair and fatalism throughout the genre. Typically, if the heroes do survive, or even succeed, they, and their world, are going to pay quite dearly for it. For example, the protagonists of Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury and The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins survive but have their lives irrevocably altered as the old world is destroyed. The protagonist of the film Brazil directed by Terry Gilliam has the ultimate bait-and-switch of imagined success for a reality in which he is literally and physically trapped in the machine but unaware of his state as fantasies of freedom are projected directly into his mind.

I will be using the term “machine-state” to refer to an ideal perfect dystopia. Though no dystopian fiction (or reality) adheres perfectly to this term, I suspect that proximity to this kind of state or societal system is the main trait that makes a work feel dystopian. The idea is stated most directly at the end of 1984 in this speech by the villainous member of the tyrannical inner party and servant of Big Brother, O’Brian:

There will be no loyalty, except loyalty towards the Party. There will be no love, except the love of Big Brother. There will be no laughter, except the laugh of triumph over a defeated enemy. There will be no art, no literature, no science. When we are omnipotent, we shall have no more need of science. There will be no distinction between beauty and ugliness. There will be no curiosity, no enjoyment of the process of life. All competing pleasures will be destroyed. But always -- do not forget this, Winston -- always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing and constantly growing subtler. Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face -- forever.3

A machine-state is an automated and self-propagating state. A kind of social construct that has become utterly entrenched in people’s minds and automated in the real world through technology and power structures. It has such a life of its own that it would keep going on even without the will of the humans who administer it. At the very minimum, it would require concerted effort by all of society at once to stop the machine. This kind of system is so stable as to be considered perpetual. It may have originated in chaos but has been refined for decades, if not generations. This system does not have major existential threats, or they are far away, or they are entirely imagined by the state. This machine is the new God, and having such threats nearby would call into question the machine’s omnipotence and omniscience. The humans living in a machine-state have absolutely no influence over the machine-state. Thus, the machine-state is totalitarian rather than authoritarian, but its totalitarianism has been refined into a high art of control over every aspect of people’s lives. If it is a truly well-made machine-state, then the way it oppresses people will be as close to arbitrary as possible. To be oppressed as part of a group creates group identity and can even be an engine of cultural production. True dehumanization destroys as much identity as it can. The machine-state is so dedicated to this dehumanization that it might not even be merciful enough to kill you when it destroys you, such as for the protagonists of Brazil, Brave New World, and 1984 who continue living as broken wretches of the system after their failed struggles.

The machine is a vast engine that generates human suffering as exhaust. To quote 1984, “The purpose of persecution is persecution. The purpose of torture is torture”. The machine-state’s purpose is not to make some people great at others’ expense, though it may also do that if convenient to the machine’s goals . The human desire for self-aggrandizement may have helped to originally create the machine-state, but human lives are completely incidental to it. It deals with socio-economic classes, not individual lives. The machine-state is a dystopia beyond the petty interests of the “great men” of human history. Human oligarchs and dictators are puppets if they exist in the system at all. The oppression of the ideal dystopia is not just systematic, but of systems. It is not just using established structures as mechanisms to operate through, but creating new structures whose very existence is oppressive.

Because this state-run hell is stable and perpetual, the machine-state is highly invested in controlling innovation. This is somewhat paradoxical given the machine-state’s basis in automated systems and power structures, but advancement creates change. Invention is a creative and highly human activity which is well known to destabilize existing systems. This is illustrated by the cases of gunpowder, the printing press, and the birth control pill, all of which rapidly altered the societies into which they were introduced. Because dystopias must control and suppress societal shifts, if any advancement happens within the machine, it will be incredibly slow and entirely controlled.

The all-consuming machine-state is an ideal in the Platonic sense, and as such, it is only more or less captured by various dystopic fictions; it is the proximity to this ideal that makes a work more or less dystopic. This says nothing about the work’s quality. The extent to which dystopias match the machine-state ideal can often be attributed to where in their history the story takes place. Aldous Huxley addresses this directly in a letter to George Orwell where they discuss which of their stories is the more likely future. Huxley speculated that the brutal society of 1984 would slowly shift towards something more like the hedonistic automation of Brave New World as the generations went by.5 The states in Fahrenheit 451 and most young-adult dystopian fiction might be thought to be early in their dystopian development, as they are often still in the process of transitioning from authoritarian to totalitarian. They cannot yet be described as full machine-states but are rapidly progressing in that direction.

History

The dystopian concept comes to authors largely from specific historical societies, which I will address in a moment, but the point of dystopia is that it is an ideal which has never been reached. Human history may be a gushing geyser of blood and suffering, but if we start labeling historical societies as dystopias, then what are the criteria for a society that is not a dystopia? Genghis Kahn slaughtering his way across Eurasia was quite brutal, but it does not call to mind “dystopic.” Historical conquerors were feeding machines, but they were feeding the machine of the warband, or a state made of interest groups (vassals, creditors, churches, etc.). In contrast to the conquerors, settled states tended more towards using depersonalized and abstract incentives (status, prestige, honor, piety, wealth, etc.). But inequality and injustice alone do not make a dystopia, nor a machine-state. Is a society dystopic specifically because it exploits its people or treats them unfairly? There is a serious problem if the answer is “yes.” Every historical society has exploited its people and treated them unfairly in some way. The variety of ways humans have invented to do this is immense. We can point at something in virtually every past system and label it dystopic.

For example, The Jim Crow South was an awful place but only held a few dystopic tendencies. It was governed by a system that was wildly inefficient and fragile. It was always hampered by the racist policies it clung to. Cutting out a huge portion of the population from the labor pool based on their skin’s melanin content cripples meritocracy, and therefore efficiency. The Jim Crow system was at all times under threat by the mere existence of the North and other countries that were doing perfectly fine without those racist policies. The oppression in the segregated South was done to create distinct groups of whites and blacks that would not mix. From a historical perspective, that is not so much a machine-state as it is run-of-the-mill human cruelty and prejudice used as tools to elevate some people above others. Terrible, but relatively dissimilar from a machine-state. It was far too inefficient, unautomated, and the dehumanization, though thorough, was targeted instead of arbitrary. Similar problems come from attempting to analyze other cruel and unequal societies, such as Imperial Rome or the Aztec Empire, as dystopias. Most historical societies, especially pre-industrial ones, were too wrapped up in particular human incentives to get close to the machine-state.

These historical problems are why the concept of the machine-state is useful as a dystopic measuring stick. So where did Orwell, Huxley, and Gilliam get their ideas? Totalitarian societies like Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, and Maoist China are perhaps the closest humanity ever came to the machine-state historically, but these were not true dystopias either. That is no defense of their actions. These were places that attempted total war and total state control of language, beliefs, etc. Fascists and communists would certainly have made machine-states if they could. Having thrown out God, their new idol was the security and order of the state through a Thousand Year Reich, or a Dictatorship of the Proletariat, or whatever other nonsense their ideologies demanded. But there is not actually such a thing as a perfectly totalitarian society. Such regimes face constant stability problems and external threats. The Nazis did not last two decades. The Soviets only made it about seven. China eventually “reformed,” though perhaps “restructured” is more accurate given current Chinese policies.6

No historical society was a true representation of the “boot stamping on a human face forever” because the world is too large and chaotic for such a system to exist indefinitely. But one thing the 20th Century totalitarians did prove is that the human spirit is in fact quite domitable. If you have industrial technology and are willing to exert enough violence, you absolutely can oppress millions of people for decades on end. Dystopia would not be disturbing if it were implausible. If every time a dictator took power they were immediately lynched by an angry mob, no one would fear dictators.

Then what could create the circumstances to bring about the machine-state? Often, dystopic writers set their worlds in a post-apocalyptic state. In these cases, the apocalypse is used as an excuse for why it is believable that society would turn in a direction that might otherwise not make much sense, and the cataclysm itself tends not to be very relevant to the work. However, many dystopic fictions do not make use of this trope or use it in an ambiguous way. After all, the world ending does not mean that it necessarily will become a dystopia; the world can simply end. Furthermore, post-apocalyptic societies are not necessarily dystopic themselves, even in cases where the government becomes tyrannical as a reaction to the catastrophe. In many fictional cases, the post-apocalyptic state becomes brutal, but without the total control of the situation required for a machine state.

Another common trope in post-apocalyptic fiction that is sometimes labeled dystopian is the radical cult. But a violent cult with a deranged leader does not a soul-crushing dystopian state make. You can escape from a cult. A cult is small enough to be existentially threatened by other groups. A cult’s power structures are not necessarily automated, or even formalized. A cult may spontaneously dissolve when its leader dies, and the cult of personality loses its personality. Cultish behavior can, however, certainly be incorporated into a totalitarian state. As an example, 1984’s cult of personality around the figure of Big Brother is fixed in place by the state and deeply entrenched. It does not matter at all if there is, or ever was, a real Big Brother. The totalitarian state of Oceania in 1984 will likely never fall and is not truly threatened by the other totalitarian powers (if they even exist) in their endless overseas proxy wars.7 Does that sound familiar?

Acceleration

So, we might say in general that apocalypse is not necessary to dystopia but would probably help things along in a society that was already on its way or even just had the right underlying tendencies. So… does ours? Have aspects of the fictional dystopias we have been reading already come to pass in Western civilization? Are they coming soon?

Yes, yes, and yes.

Contrary to popular belief our society is a very pleasant place to live. Relative to anywhere in the past, and most places in the present, it is truly incredible. Yet everyone incessantly complains, and we are certainly not acting like people living at the utter pinnacle of human history. How strange. Of course, much of that can be chalked up to the indomitable human capacity for whining. But the question remains, why are people so dissatisfied with our society when quality of life is orders of magnitude better than it was just a century or two ago?

I am not about to make the claim that America is a machine-state like what I have previously described. The government is not dedicated to dehumanization for its own sake. The police and military are usually trying to get something out of the people they torture. I am instead making the claim that we are in something very similar to the machine-state I previously described, but without the inefficiencies of sadism. Not a benevolent state by any means, and not lacking inequality and violence, but closer to ambivalent than malevolent.

This is largely due to inevitable historical forces around effects of technology including globalism, industrialization, the nuclear bomb, and the information age. Many voices call capitalism a dystopia or claim we must never give an inch to communism as that would be a dystopia. Phrases like “X wants 1984!” and “Y will lead us into a Brave New World!” get bandied around so much in party politics as to make them almost meaningless. These perspectives miss the point that what is currently making the world dystopic is the circumstances of modernity in general, not the actions of a particular group. There are of course “immoral” and exploitative people and groups, but that is always the case in every place and time. Why are those people’s actions now creating dystopia?

An important part of this is because, in a sense, we are at the end of history.8 The United Nations (UN), globalization, and more than anything, the atomic bomb, have frozen the recurring great power conflicts of history. Until the last four generations or so, war was not one or more great powers influencing a conflict in a weaker nation. War was the great powers of the world destroying entire generations of each other’s young men every 30 years or so. The state of mutually assured destruction brought about by the bomb, and the diplomacy built on top of that foundation, is what changed things. Now, despite many modern nations having been quite poorly defined at their creation, the general international consensus is that, for the foreseeable future, everyone needs to stay in their assigned seats. We label the countries that do not as the “bad guys” because they are either trying to go back to, or restart history.9 That sounds an awful lot like the stability and lack of existential threats of the machine-state.

The ideologies of these stable great powers interact with technology in a particular way. During the Cold War, communism and capitalism’s claims of superiority over each other were often based on being the greater industrializer and better at advancing technology. There is a reason NASA’s greatest levels of funding were during the Space Race.10 Both ideologies were founded on technological accelerationism. Both were dedicated to automation and efficiency as virtues. They both worked under the assumption that a more connected and technologically sophisticated world would be a better place. The irony of two states who almost destroyed the world multiple times, enabled by modern technology, believing that technology would improve the world is incredible.

The ideology of these states does not truly matter. A system with a more or less socialist economy or that is somewhat more or less respectful of civil liberties does not fundamentally change the bigger picture of our century. How much do domestic policies truly matter when supposedly diametrically opposed ideologies engage in the same forever wars abroad, have the same goals, and measure success in the same way?

Alienation

Industrialized society is broadly stable and technologically advanced. So what? Is that not a good thing? Well, industrialized society is also extremely alienating and dehumanizing. This is not a recent development. Marx pointed out aspects of this in the mid-1800s with his Theory of Alienation. Marx got a lot of things wrong (like advocating mass murder), but his theory of alienation was accurate, though incomplete. Workers feel alienated from their labor because they “… had less control over their work, were often unskilled, and were often just part of a production line.”11 Basically, workers make products they do not control for people they do not know, for a benefit they do not personally derive. Or in Marx’s own words:

The worker puts his life into the object; but now his life no longer belongs to him but to the object. Hence, the greater this activity, the more the worker lacks objects. Whatever the product of his labor is, he is not. Therefore, the greater this product, the less is he himself. The alienation of the worker in his product means not only that his labor becomes an object, an external existence, but that it exists outside him, independently, as something alien to him, and that it becomes a power on its own confronting him. It means that the life which he has conferred on the object confronts him as something hostile and alien.12

What Marx implied, but many of our dystopian writers picked up on directly, especially E. M. Forester’s hyper-automated world in The Machine Stops, is that industrialization alienates us from everything around us, not just our labor.

We do not notice this alienation and dehumanization because we were born into it, molded by it. To us this is just the way the world is, but we can train ourselves to notice it again. Look around the room you are in right now. Do you know the origin of a single object within view? Not the store where it was bought, but where it was made? What percentage of the objects you own were made by someone you have met? When was the last time you ate something grown by someone whose name you knew? We are dependent on a lot of technology. How well do you understand the systems of plumbing, architecture, engineering, electricity, infrastructure, computation, and networking which you use every single day? The point is not that being specialized and out-sourcing is necessarily a bad thing, industrialization happened for a reason, but living in such a detached world is alienating, nonetheless.

The fact that life is quantitively better on almost every metric since the Industrial Revolution is the most important part of the technological trap of our state-machine. How could anyone advocate regressing technology and de-development? “I don’t want to feel alienated, therefore you can not have your smallpox vaccine or your tumor MRI,” is a completely insane and indefensible statement. That said, some people, such as the infamous Ted Kaczynski (AKA The Unabomber) have advocated exactly that position.13 Like Marx, Kaczynski was wrong about many things (like advocating mass murder), but he represents one genocidal extreme end of a discourse between primitivism and technological accelerationism. On the side of accelerationism is techno-capital (the state and business interests pushing forward technological development) and its unfettered dehumanization for the sake of profit. Managing our relationship with techno-capital is perhaps the most broadly important issue of the 21st century.

Current party politics are totally oblivious to this discourse and appear generally uninterested in addressing techno-capital, perhaps this is a function of techno-capital. Except for when the Left occasionally remembers that climate change exists and the Right conveniently notices the erosion of social values, our unending progress is seen as an unambiguous good. Consciously addressing techno-capital and finding a way forward away from both extremes ought to be the dominant theme of societal discussion. Fortunately, new generations appear to see these themes somewhat more clearly.

In terms of technology and automation, the machine-state has already won. All of society is based around technological advancement. Just like in a machine-state, the technology and the power structures supporting the machine have been almost completely automated to propagate themselves. No Kaczynskian anti-technology mass movement will ever be able to effectively fight the forces of techno-capital because they will always have worse technology. There is also the problem of trying to convince most of the population to give up their cell phones, hospitals, and mass-produced agriculture. It would take apocalyptic events to alter the course the world is on.

Quite unlike a truly dystopian machine-state, our system is based on ever increasing acceleration. Though this is perhaps the main feature distinguishing our society from the perpetuity of a machine-state, such unchecked progress could eventually steer into the mouth of a true dystopia. Our system does not stymy change unless it directly conflicts with its interests. It is entirely foreseeable that humans could eventually begin space colonization and bring the machine-state along with us.

We cannot uninvent the combustion engine, condom, or the internet, despite the massive, often negative, but always chaotic effects these things have had. Who would want to? These things may have disrupted previous ways of life, but they were adopted because they confer incredibly useful advantages. History has proven that we can at best regulate some kinds of advanced research. A great example is that of the greenhouse effect and global warming. It was already known in the 1800s by multiple scientists that this could become a problem.14 Society was not even based on the combustion engine yet, but nothing was done to stop or regulate it at all until relatively recently. No one has a choice in living in a world impacted by carbon emissions. Reduce your carbon footprint to zero and you still have to breathe the exact same pollution as before. You have no incentive besides principle to stop polluting. Humanity is going to advance because technological progress is one massive tragedy of the commons. Pausing is not a realistic option and going back even less so. Techno-capital will never allow it, but more importantly, we will never let ourselves.

Hell’s Silver Lining

We did not choose to be born into these circumstances, but here we are. To not accept that humans have the incredible technological power we have achieved is to ignore the world’s thrown state. If we pretend that we are not holding a gun, because guns are frightening, then we can never holster it. While we exist within our machine-state, we will need to adopt new attitudes to move forward and perhaps avoid dystopia.

The conundrum of intervention and technology when it comes to the environment is typical of the modern world. The eventual solution will have to be moderate. Completely removing human impact is impossible, unless you are willing to adopt the genocidal attitude of a Kaczynski. Even magically eliminating human impact would not remove the impacts we have already had anyway. Completely fixing the situation through more technology is impossible, even assuming we could create technology to stop all the present harm. Moderation and conscious management are the only semi-realistic solutions.

That all sounds quite negative, but it is not cause for total despair. Our machine-state is very different from those of Orwell and Forester. As stated, our technological advancement brought us into this position, but that progress also keeps our society chaotic and creative. Humans may struggle to keep up, but so does the state.

In many ways modern states are far more responsive to the wants of their citizens. The state is quite good at keeping people from violent revolt and generally distracted with the meaningless issues of party politics. Mass surveillance and a bloated military allow the state to go after particular groups and individuals, typically through overseas forever wars or the prison-industrial complex. Yet, despite the general perception, when the public cares a lot about something, the political machine sometimes changes its behavior. How few casualties in one of our forever wars does it take to make the news and cause controversy? Single digits.15 Compare that with the massive wars of centuries past in which the public had virtually no say. How many police departments reformed after BLM protests? How quickly do such protests organize after a new viral story? How long did people accept January 6? It seems like that kind of coup attempt would have been far more likely to succeed a century or two ago. In the past Epstein Island might have been only known through vague rumors and never exposed, like Capri under the Roman emperors.16

Perhaps it feels like democracy has become a performative farce. That is likely because it was always a performative farce and is only now revealed as such by the information age. But also, thanks to the information age, the surveillance state can be a little bit bidirectional. Entire populations can create a consensus opinion and generate unrest within hours of events happening. Public figures are scrutinized as never before. One effect of the complete loss of personal privacy is a state aware of its denizens in a way no state has ever been before. With social media this does not even require active purposeful tracking. People will go out of their way to let the public forum know exactly what they think and want. Though systemic revolution is now impossible, democracy might be the least farcical it has ever been. Reforms are usually meaningless, but not always. Incremental change is change.

We are frightened by the inevitability of technology and the way it is creating an unsettling level of interconnectedness. This is a rational reaction. This change has never happened before and things that have not happened before are often dangerous. The techno-capital interests of the world are pushing as hard as they possibly can through social media and now AI. There are many negative consequences of this, and some people worry about the potential for singularity and hiveminds.

This may be a strange position, but I propose that humanity has always been a sort of hivemind, just a very slow one. In a way, the fact that culture exists at all is a hivemind. Humans can transfer ideas, archetypes, and memes across our large neural network (culture) from node to node (our induvial brains) through speaking and writing. We can even do it across generations. We are so accustomed to this that we do not notice it happening most of the time. Consider how incredible that ability is and that we are the only species that can do it. From a very broad view, the whole planet is a brain with individual humans acting as neurons. Through the internet, culture is now processing ideas and themes that would have once taken generations in just years. That was once a bizarre idea, but the rise of a global internet culture has brought it close to a reality. That is a very different reality from what we know, but perhaps not an intrinsically hellish one.

The previous paragraphs will not assuage most people’s fears. They probably shouldn’t. In this paper I have attempted to define the perfect utopia and found our state to be distressingly similar. Perhaps this state of affairs was inevitable. The future is going to get much worse in a variety of ways. It is also going to get better in some, and maybe many ways. If we refuse to acknowledge our situation, then we can do nothing and a sadistic machine-state in the style of Orwell, Forester, and Huxley is inevitable. But we can adapt to our circumstances. We cannot completely change or destroy the machine. We may not even wish to. Living in a world with neither world wars nor atomic apocalypse is not the worst possible outcome, so long as we can keep that balance. Although we may not be able to escape the machine, perhaps we can learn to adjust it. Perhaps the boot stomping on a human face forever in 1984 does not have to stomp the same way forever. Perhaps it can become a boot stomping the ground as it walks forward instead. 17

I think there is something inherently beautiful in simple shapes. In simple shapes there is no obscuring the light and shadow. Nor any flashy tricks. There is only simple values and gradients surrounding their thresholds.

Sweep, clean, swap

Wash, fold, swap

Sweep, clean, swap

Wash, fold, swap.

And endless cycling routine

Still, away I run and run

desiring an open door.

Again, I’m caught

—With no escape

Dragged unto a lifeless chore.

Sweep, clean, swap

Run, run, run

Wash, fold, swap

Run, run, run

A shell of what once was.

Captive to humanity’s pressure

Yet, I yearn to be set free

From this prison’s social clock.

After using oil paints for the first time, I realized the incredible potential that the medium has. Its ability to blend is unmatched, and its slow-to-dry nature allows for adjustments regardless of breaks between painting. That's when I decided to paint "fallen angel". I wanted to challenge myself to do a piece that was more detailed than anything I had ever done before. In addition, I wanted to create a piece that juxtaposes itself, having deeper meaning than what meets the eye. The angel, a mythologically divine being, is surrounded by blood that isn't his own, and his wings have been tainted by sin. What he has done, however, is up to the viewer, because I believe that in every piece of art it is the right of the onlooker to develop their own interpretation.

In this essay, I will delve into the article In Defense of Design, written by Mark Foster Gage. The article focuses on how art has gone from simplicity to interpretation. He mentions that a line is no longer allowed to be a “mere line” and, in turn, must have a story or a “rationale” for its “straight-laced life.”1 The article also focuses on architectural design as a way of problem-solving.

In the second page of the paper, Gage mentions an article written by David Gissen, titled “Architecture’s Geographic Turns.” He mentions Gissen’s article as a bridge into architectural design as a way of problem solving, or more specifically, the “theoretical surge of research architecture.” Gissen goes on to explain that research architecture is an act of “architectural theory,” not one of design.2 The boundaries between a theory and a practice of “research architecture” are disestablished. These boundaries are only capable of providing in restricted conditions, often less demanding. They force geographical design to lose its aspect of simplicity and turn into describing the circumstances around the buildings rather than the building itself.

In this essay, I will delve into the article In Defense of Design, written by Mark Foster Gage. The article focuses on how art has gone from simplicity to interpretation. He mentions that a line is no longer allowed to be a “mere line” and, in turn, must have a story or a “rationale” for its “straight-laced life.”1 The article also focuses on architectural design as a way of problem-solving.

In the second page of the paper, Gage mentions an article written by David Gissen, titled “Architecture’s Geographic Turns.” He mentions Gissen’s article as a bridge into architectural design as a way of problem solving, or more specifically, the “theoretical surge of research architecture.” Gissen goes on to explain that research architecture is an act of “architectural theory,” not one of design.2 The boundaries between a theory and a practice of “research architecture” are disestablished. These boundaries are only capable of providing in restricted conditions, often less demanding. They force geographical design to lose its aspect of simplicity and turn into describing the circumstances around the buildings rather than the building itself.

Because of this change, there is an expectation that analysis is needed to show validity in architectural design. But just because something can be mapped does not mean that it can produce answers. Throughout the analyses made by research architecture, they are unchallenged and “mistakenly assumed to be efficient.”3 The practice of research architecture is no longer a practice; instead, it allows designers to accomplish said architecture without human will. It is rather robotic. Those in charge of architecture now focus on the masquerade of evidence with a regimen of diagrams filled with useless information.

Gage goes on to write that the new precedent of architectural design focuses on the wrong things. Current architects yearn for information, and shortcuts per se, rather than former architects who demanded knowledge and a full understanding of the historical lineage of architecture. Current architects are just simulating alternate routes of architectural design.

Architecture today is so immersed in the “why” as well as having a “foundation of ‘hard’ data,” all “to justify design.”4 Gage argues that current architecture is in no position to require such data as justification of design, regardless of credibility.

Gage also writes that people today are so obsessed with problem-solving to create a “repeatable working method” rather than face a “blank sheet of paper.” He questions his readers as to why this is the new criterion, asking if it is easier to teach repetitiveness rather than “precedent.” Those in research architecture are trying to avoid a legitimate rationale by using a continual replication of those before them. He explains that architecture needs freedom to have creativity and “not-always justifiable decisions.” This does not mean that architecture should be mindless, but it cannot primarily emerge from such incessant acts.5 Architecture commonly assumes intellection as a basis of production, discrediting intuition as a form of intelligence.

Rules should often face deviation in the world of design. Current regimens should be challenged and should not replace the ability to think instinctively. Architecture needs to consider “new things (rather) than problems.”6 Architecture needs speculation, allowing it to become more than a way of problem solving and repetition. Research architecture is truly a construct, something many will never understand. Research architecture takes away the art from architecture that is needed for creativity to thrive.

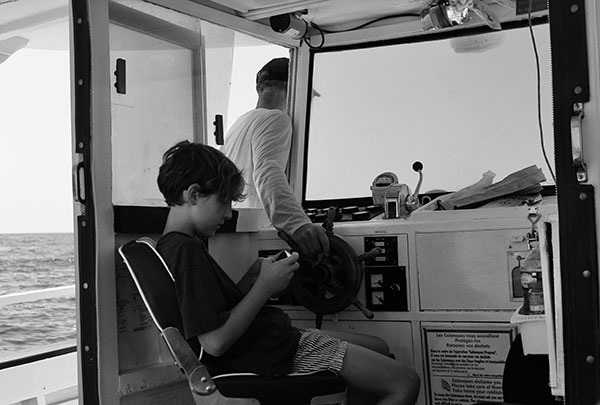

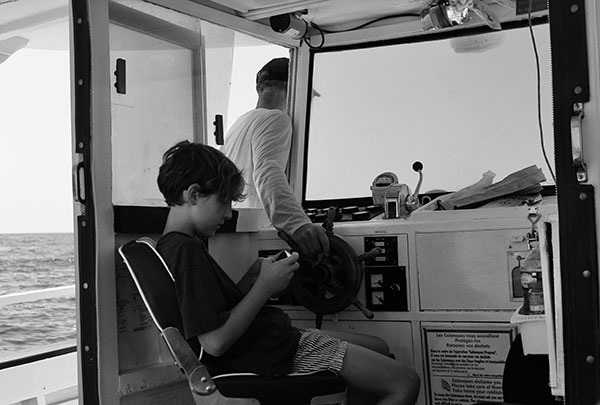

I captured a moment on a boat in France that struck me. Our captain was calm as he navigated the waters, his steady hand stretched back and guided the vessel with confidence. In the captain’s chair, his grandson sat absorbed in his phone, despite the surrounding beauty. This image made me contemplate: In this age of distraction, are we missing out on the life we have right in front of us? It seems that more value is placed on our engagement with videos, pictures, and ads than our engagement with reality. The most important decision we can make is how involved we want to be in our own lives.