What does it mean to be asexual? While often misunderstood, asexuality is a valid and multifaceted identity within the LGBTQIA+ community. This is often confused with the closely related aromantic label, where an individual feels little to no romantic attraction. Many people believe love cannot exist without sex and that romantic and sexual attraction must always be intertwined. However, as someone who identifies on the asexual, or “ace,” spectrum myself, I’ve found that there are many ways to experience love, whether it be romantic, platonic, familial, or otherwise.

What does it mean to be asexual? While often misunderstood, asexuality is a valid and multifaceted identity within the LGBTQIA+ community. This is often confused with the closely related aromantic label, where an individual feels little to no romantic attraction. Many people believe love cannot exist without sex and that romantic and sexual attraction must always be intertwined. However, as someone who identifies on the asexual, or “ace,” spectrum myself, I’ve found that there are many ways to experience love, whether it be romantic, platonic, familial, or otherwise.

Looking back, I now realize how my religious upbringing shaped my early understanding of attraction and relationships. Purity culture is a key principle in my religion’s teachings, and I was taught to view physical desires as both sacred and unclean. Because I had never felt sexual attraction, the constant admonitions from church leaders to “remain virtuous” never seemed difficult to follow.

“This will be easy,” I thought. “I’ve never felt that way about anybody!”

If only I could travel back in time and tell my teenage self what I know now.

I first encountered the term “asexual” as a human sexuality when a young author I admire, Lancali, openly discussed her identity. At first, I was unsure of what the label meant and assumed it couldn’t possibly apply to me. I thought romantic and sexual attraction was the same thing, and although I squirmed at the idea of what was expected to happen on a wedding night, I still had a strong desire to be in a romantic relationship.

It wasn’t until after I read Alice Oseman’s Loveless that I started to understand the word “asexual’s” meaning. The book follows Georgia Warr, a college Freshman navigating her newfound aromantic asexual, or “aroace,” identity as she learns to value platonic relationships as much as romantic ones. As Oseman is aroace themself, their personal experience helped them create a relatable protagonist who positively represented their orientation.

Reading Loveless right after high school felt incredibly timely, as I was beginning to reflect on my own identity and what awaited me in university life. Through Loveless, not only was I able to get a glimpse into what college is like for young adults, but I also solidified my confidence in my asexuality while reading about Georgia’s joys and struggles.

I was relieved to learn that there are other people who experience love in a nontraditional sense, but it could be isolating at times to watch couples getting married and raising children in a way I wouldn’t necessarily have or want. I still dreamed of having a supportive partner to go on bookstore dates with and talk to about all my joys and challenges in life, but I knew I would never have the same kind of relationship allosexuals—a term for people who aren’t asexual—considered normal. Would I ever find people like me outside of internet forums? Would I ever meet someone who loved every part of me, asexuality and all?

Amid my anxiety, I developed a support group that made accepting myself much easier. When I came out to my best friend, she told me she had already done plenty of research on asexuality on her journey toward discovering she was bisexual. I found out that someone else I’m close with is also on the ace spectrum, and I was ecstatic to find a person I knew in real life who had similar experiences to me whom I could relate to.

As time went on, I learned about microlabels and the nuanced beauty that is the asexual spectrum, whether an individual be sex-repulsed, sex-neutral, sex-positive, or another label they prefer. I also discovered two other labels that fall under the ace spectrum: graysexuality and demisexuality. A graysexual individual only feels sexual attraction occasionally or to a low degree, and a demisexual person needs to form a strong emotional bond with their partner before feeling any kind of sexual attraction.

I learned to value the fluidity of sexuality, understanding it would be normal for my perception of my orientation to evolve throughout my life. As I’m not aromantic, I’ve gone back and forth between identifying as bisexual and lesbian, which can be a confusing process. Labels may be a source of comfort for many, but there are no rules saying anyone needs to put themselves in a box and explain every detail of their identity to everyone who asks. As a quote from Benj Pasek and Justin Paul’s musical, Dear Evan Hansen, says, “Today at least you’re you, and that’s enough.”

I still face many challenges in a world where sex is prioritized above emotional intimacy, and I often find myself arguing with others about the validity of my orientation. Despite all of this, I’ve found peace in the asexual community. By sharing my experiences and writing ace-spec characters in my future novels, I hope to increase awareness and representation for those who, like me, may have struggled to find themselves in mainstream narratives. Society’s strict expectations for relationships cannot limit the many ways humans feel love.

It was a spring day when I found this pond. I adored the reflections on the water, and how the ducks would disturb the surface when they’d land or take off. I tried strenuously to make sure the scene felt balanced. Whenever I look at this photo, it takes me back to the moment it was taken; I can almost feel the crisp air and hear the birds flapping away.

In a letter written to his younger sister on March 30th, 1772, Benjamin Franklin mentions, "She has shown me some of her Work which appears extraordinary. I shall recommend her among my Friends if she chuses to work here."¹ This woman mentioned in Benjamin Franklin's letter can be identified as Patience Lovell Wright, or Mrs. Wright, as Franklin commonly called her. The "extraordinary" work that Franklin refers to just so happens to be Wright's collection of wax sculptures of well-known political figures. These sculptures are why Patience Wright is recognized as America's first and one of its finest sculptors.² During her life, Wright proved herself instrumental in building the new nation through the artistic traditions she developed and through her support of the revolutionary cause.

In a letter written to his younger sister on March 30th, 1772, Benjamin Franklin mentions, "She has shown me some of her Work which appears extraordinary. I shall recommend her among my Friends if she chuses to work here."1 This woman mentioned in Benjamin Franklin's letter can be identified as Patience Lovell Wright, or Mrs. Wright, as Franklin commonly called her. The "extraordinary" work that Franklin refers to just so happens to be Wright's collection of wax sculptures of well-known political figures. These sculptures are why Patience Wright is recognized as America's first and one of its finest sculptors.2 During her life, Wright proved herself instrumental in building the new nation through the artistic traditions she developed and through her support of the revolutionary cause.

In 1725, Patience Wright was born in New Jersey to Quaker parents. She spent her childhood in Bordentown and Long Island and married Bordentown resident Joseph Wright in 1748, soon having between three and five children with him. Not much is recorded or known about her life before her marriage, and questions thus arise about where her sculpting skills came from. There would have been no examples of sculptures nor sculpting instructors in the small Quaker colony, meaning Wright was likely self-taught. While her artistic development is often debated, some scholars believe she learned the trade by sculpting faces in clay and bread dough. Regardless of her training, she began to gain a positive reputation for the likeness she could capture in her wax figurines.

When Wright’s husband passed away in 1769, she had to figure out how to live as a widowed mother. To make a living, she looked towards her sculpting skills. Accounts claim that “[Wright]… showed a decided aptitude for modelling, using dough, putty, or any other pliable material she could find, and being left by her husband with scant means, made herself known by her small portraits in wax.”3 Not only was wax a more affordable option for sculpting, but its malleability and translucent nature made it perfect for replicating the details and capturing the likeness of the models. Wright took the nature of this medium and used it to her advantage, traveling around the East Coast to fulfill portrait commissions before eventually settling in New York.4 There, she continued to fill commissions and sculpt for lesser-known political figures, such as her wax and wood profile bust of the American Admiral Richard Howe (fig. 1).

In 1771, a fire melted and destroyed many of Wright’s works, and she looked towards Europe for a new start. In Europe, wax sculptures were gaining popularity as the public found fascination and curiosity with the illusionistic nature of the medium. Not only was the popularity of wax spreading, but many female artists were finding success sculpting with it.5 Wright took the knowledge and skill she had built in the United States and, in 1772, made her way to London with her children. In England, Wright capitalized on the popularity of wax figures that was not entirely present in the United States. She sculpted British subjects and created full-body sculptures, life-size busts, and smaller profile busts, all from wax. She began to pick up acclaim, which is evident when Dunlap mentions that “There is ample testimony in the English periodicals of the time, that her work was considered an extraordinary kind; and her talent for observation and conversation… gained her the attention and friendship of many distinguished men of the day.”6 In her first year in London, Wright began sculpting for Jane Mecom, the sister of Benjamin Franklin, who lived in Europe at the time. It was then that Wright started gaining recognition from important political figures in the United States, as is evident by her “extraordinary” talent, voiced by Franklin in his previously mentioned letter.7

While in England, Wright not only started gaining widespread popularity among American audiences, but she also began developing a fervor for the revolutionary cause occurring in the colonies. Toward the beginning of her time in London, Wright had built a good relationship with King George III of England and his wife Charlotte, even having them sit for her. However, as the revolution went on, she began to lose trust in them. She was said to have believed “that the king was personally responsible for the war and that the institution of monarchy was politically unjust.”8 She continued to work for the British population. Still, as she sculpted them, she would listen closely to their discussions of political gossip and military matters. Wright would then pass this information to American correspondents, warning of British military plans and encouraging the colonies to stand firm.9 These messages were primarily passed through letters, but some argue that Wright even hid warnings in the wax sculptures that were shipped to the colonies. While the exact benefit of her warnings has not been identified, it is assumed that they gave some aid in making preparations for the revolutionary troops.

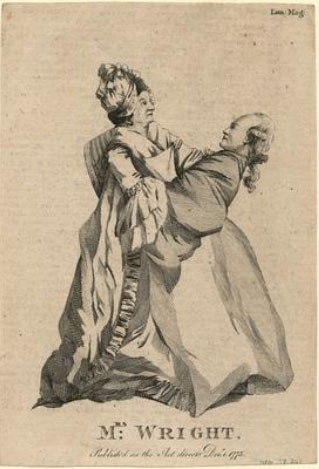

While contributing to the revolutionary cause, Wright continued to gain acclaim for her sculptures while in England. She fulfilled American and British commissions, creating images of well-known political and diplomatic figures. While few of her works from this time have survived, her style and skill can still be seen in her profile bust of Benjamin Franklin, which was created in 1775, and her full-body wax sculpture of England’s Prime Minister, William Pitt, created between 1775 and 1778 (fig. 2 and fig. 3). As Wright continued to sculpt, audiences showed increasing fascination with her unique and realistic creations. This fascination can be seen in the print titled Patient Lovell Wright, created at the height of Wright’s popularity in 1775 by an unknown artist (fig. 4). It depicts Wright holding a male figure who appears to be relatively lifeless. Upon looking closer, viewers can realize that the figure is one of Wright’s Wax creations, but it appears so realistic that it is challenging to determine whether or not it is an actual person.10 This print provides a clear example of how the public was impressed and transfixed by the illusions that Wright created through her waxwork.

Despite the acclaim that Wright had gained in London, it was challenging for her to reside there as a supporter of the newly formed United States. Because of this conflict, she temporarily moved to Paris in 1781, where she likely spent time building a new client base and further developing her sculpting skills.11 After some time away, she returned to England in 1783 and continued painting British subjects. During this time, she also began connecting with George Washington, corresponding with him in letters and sculpting a profile bust of him from between 1784 and 1786 (fig. 5). In these letters, Wright expresses her hope to come back to the United States, telling Washington, “… it has been for some time the Wish and desire of my heart to moddel a Likeness of generel Washington… and Return in Peace to Enjoy my Native Country.”12 While Wright was grateful for the work that she accomplished in England, she longed to return to the United States, where she had not been since she had moved eleven years before. Months later, Washington responded to Wright’s letter, acknowledging her sentiments and praising her work. In his response, he remarks, “… and if your inclination to return to this Country should overcome other considerations, you will, no doubt, meet a welcome reception from your numerous friends: among whom, I should be proud to see a person so universally celebrated.”13 Through these words, it is clear that even Washington, one of the most celebrated men in American history, praised Wright’s work and hoped to see her return to the country, showing the wideness of her reach.

Unfortunately, while Wright hoped to return to the United States, she suffered a fall in 1786 and passed away soon after.14 Although she could not return to the United States, she was still able to make a lasting impact on the American art world. As the new country developed, Americans sought to create a new art vocabulary to define their nation. Patience Wright was able to help with the development of this artistic vocabulary, opening the door to the unique medium of wax and creating realistic sculptures that documented the new nation’s most important political leaders. Her impressive sculptural techniques would be looked upon for generations to come as examples of artistic genius. As long as American sculpture continues to exist, Patience Wright’s legacy and her role in sculpting the nation’s art will live on.

These photos, taken in Athens and Pentalofos, Greece, are part of an international project between UVU Digital Media, UVU Architecture, the National Technical University of Athens, and the Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens. Our goal was to study Greece’s architectural styles and document the endangered craft of stone masonry in Western Macedonia, a tradition dating back to the 7th century.

Rather than simply preserve the past, we aimed to celebrate it. The homes in Pentalofos, built by master stonemasons, carry stories in every stone. Through our work, we hope to keep those stories alive and inspire others to see the beauty in what still remains.

All three were shot on a Sony ILCE-6400 with an 18-105mm F4 G OSS lens.

Still Standing, Still Stubborn: The Acropolis Watches All

This was taken off the path from the Acropolis, which translates to "high city," it stands over the city of Athens as a monument created in an era long since passed. You can see where people enter and how the Parthenon is filled with scaffolding from the ongoing effort to preserve the structure.

Details in the Dust: The Parthenon Up Close

Snapped just before entering the Parthenon, right before I was scolded for using a lens that—apparently—looked suspiciously professional. If you look closely, you'll notice the subtle color variations in the marble. These are intentional; preservationists use stone sourced from local quarries to reinforce the structure while preserving its historical authenticity, a quiet tribute to the craftsmanship that's kept it standing for over 2,500 years.

Elders of Olympus

A few of Pentalofos' finest (lovingly dubbed our “seasoned gentlemen”) posed proudly after shouting “Pentalofos!” at us from the town square. They had gathered to watch us fly drones over the village, cheering us on every time we managed to land without incident.

Honors Submission Essay

I walk down the street, marveling at the complexity of the city around me. New Orleans is an incandescently beautiful city. It is home to varieties of music, dance, literature, and art that encompass the melting pot of a city in one enormous hug. On every street corner I walk by I find musicians playing jazz music or artists selling their work. I take photos of it all.

I round a corner and run into a small library. I stop for a breath and marvel at the countless works displayed on the shelves. The shopkeeper smiles at me from the window and beckons me inside, but I stand contently on the outside of the shop reading the multitudes of titles the books throw at my face.

Books are like that, you know.

They suck you into imaginary worlds crafted from the delicately alluring mind of a stranger somewhere in the world. They take you places you never even dreamed of and allow you to form connections with the most unique of characters who seem to become real, if only in the darkest corner of your mind. Books are adventure. They are a deep breath after being submerged in the chaos of everyday life.

With a small wave at the shopkeeper, I walk down the rest of the block, thinking about the multitudes of worlds I have traveled to in my mind.

— One Year Later —

New Orleans. Destroyed. Only the lucky survived.

I trudge down the once-bustling streets, looking for opportunities to help others and freeze.

There.

Right there once stood a library full of stories, now lying in ruin. In rubble. I snap a picture and a sharp pang of grief pierces my soul for the loss of art. The world needs to know that without literature, we are lost.

Chris Jordan, In Katrina’s Wake. Princeton Architectural Press, 2006.

It was a vibrant, snowy day, and I wanted to get out and take some photos of the freshly fallen snow before it melted or got blown around in the wind. There were so many clouds, and I liked how the light and shadows interacted with the snow to make some of the patches of snow look like clouds.

Breath, a basic life function, holds an interesting place in popular culture, regarded in equal parts with romanticism and disdain. One may take a refreshing breath of sweet spring air in joyous recognition of the wonders and beauty of life and nature. Or, one can waste a life away doing little more than breathing. As Tennyson puts it, “How dull it is to pause, to make an end, to rust unburnished, not to shine in use! As though to breathe were life!”1 Regardless of such popular notions of breath, the activity, if it can be called such, is a crucial part of proper singing. As pedagogue Julia Davids and psychologist Stephen LaTour note, “breathing is the foundation of singing.”2 Without a properly drawn and expelled breath, one cannot sing with proper phonation, resonance, or vitality. In order to sing well, then, it is important to know how to breathe well. Despite its importance, or perhaps because of it, there is a wide range of opinions on the proper ways to breathe within the context of singing. In regard to exhalation, for example, some, such as Richard Miller, favour the Italian appoggio technique.3 Others favor a contraction of the abdomen, or an outward distention, or even that the singer does little at all to retain or push out the air.4 With so many differences of opinion from a variety of reputable sources, one might wonder which technique is most effective in the process of producing good singing. This paper will attempt to examine the benefits and drawbacks of the variety of opinions in literature, in order to find the most optimal method of breathing.

Breath, a basic life function, holds an interesting place in popular culture, regarded in equal parts with romanticism and disdain. One may take a refreshing breath of sweet spring air in joyous recognition of the wonders and beauty of life and nature. Or, one can waste a life away doing little more than breathing. As Tennyson puts it, “How dull it is to pause, to make an end, to rust unburnished, not to shine in use! As though to breathe were life!”1 Regardless of such popular notions of breath, the activity, if it can be called such, is a crucial part of proper singing. As pedagogue Julia Davids and psychologist Stephen LaTour note, “breathing is the foundation of singing.”2 Without a properly drawn and expelled breath, one cannot sing with proper phonation, resonance, or vitality. In order to sing well, then, it is important to know how to breathe well. Despite its importance, or perhaps because of it, there is a wide range of opinions on the proper ways to breathe within the context of singing. In regard to exhalation, for example, some, such as Richard Miller, favour the Italian appoggio technique.3 Others favor a contraction of the abdomen, or an outward distention, or even that the singer does little at all to retain or push out the air.4 With so many differences of opinion from a variety of reputable sources, one might wonder which technique is most effective in the process of producing good singing. This paper will attempt to examine the benefits and drawbacks of the variety of opinions in literature, in order to find the most optimal method of breathing.

Posture

If good breath is the foundation of good singing, good posture is the foundation of good breath. As Davids and LaTour note, “correct [singing] posture elevates the ribs, allowing greater lung expansion and finer control of breathing.”5 Elevating the ribs through correct posture does two things. First, it permits the ribs to expand more fully during inhalation, allowing for a deeper breath. Second, by elevating the ribs, the abdomen is able to expand further, also allowing for a deeper breath. There are other benefits to correct posture. Again from Davids and LaTour,

without proper posture, muscles that can affect vocal production must compensate to maintain body position. Tensing of the muscles [particularly those muscles that compensate to maintain body position] degrades sound quality. Moreover, singers with poor posture tire easily because they spend too much energy on maintaining balance.6

Posture’s importance, then, for breathing and singing is quite substantial, allowing both a full breath and a relaxed musculature. Both the full breath and relaxed muscles mean that the singer tires less quickly, both because of the lower frequency of breaths requiring less work in inspiration and because of the removal of excessively tense muscles.

Not all the literature agrees on the crucial importance of good posture, however. Vennard argues that “it is easy to overemphasize posture … Opera singers demonstrate continually that there is no one posture that is the sine qua non of good singing.”7 In many ways, Vennard is correct in this assessment. While onstage, opera singers are often moving in ways that are not entirely conducive to “proper posture.” In fact, they are required to do so in order to operate at the top levels of opera performance, bending at the waist, standing on the balls of their toes, sitting, laying down, moving about wildly. This being said, however, such movement is rarely so exaggerated that the singer substantially diminishes their ability to fully expand the lungs or tense muscles that diminish vocal quality. In fact, movement that does such things is actively discouraged by many directors. If an opera requires exaggerated movement that diminishes breathing ability, these things are often done when singers are not actively singing.8

If good posture is such an important element of good breath, and therefore good singing, how does one achieve good posture? Feet should be spread a shoulder’s width apart, directly underneath the pelvis. Some argue that one foot should be slightly in front of the other to eliminate the tendency to sway side to side.9 This is perhaps an overly simplistic solution to an issue that could be solved through better acting during singing, if it is indeed a problem at all. After all, if one has one foot too far ahead of the other, it may lead to tensing of those same muscles that poor posture tenses, leading to an inferior vocal production. Some, such as Davids and LaTour, argue for even weight placement across the whole foot, favouring neither ball nor heel.10 Others, such as Marilee David, argue that one should place more weight on the balls of the feet.11 The great benefit of placing more weight on the balls of one’s feet is there will be less of a tendency to lock the knees, so this may be more advisable, particularly for new singers. But the question of weight distribution is perhaps not so important an issue.

Moving up the body from the feet, one should have a straight back such that the hips, chest, and head are all in a straight line.12 The sternum should be elevated, but not exaggeratedly so. All this will work in unison to ensure that the weight of the body is being directed perpendicular to the floor, allowing the legs and spine to bear the weight of the body, rather than abdominal, back, and neck muscles. The shoulders should be back, but not forced so. To simplify all these steps, Vennard compares this posture to “a marionette, hanging from strings, one attached to the top of your head and one attached to the top of your breast bone.”13 This is a very effective visualization, one commonly used in theatre as well as classical singing; though it may at times be easy to forget the second imaginary string attached to the breast bone, leaving a less elevated sternum and more forward shoulders.

As David notes, however, “posture is highly individual.”14 While the physiognomy of the human race is largely the same, there are minor variations that will result in good posture looking slightly different from one person to another. The important principle to remember is that one should have space to fully expand both the abdomen and rib cage during inhalation, while not being so rigid in the effort of maintaining good posture that the muscles are tensed in a way that inhibits quality vocal production. Once one has created a good posture which feels open and comfortable, it is time to look toward the act of breathing itself–in particular, the inhalation.

The Anatomy of Inhalation

As the late Baroque singer and teacher Gasparo Pacchierotti noted, “chi sa ben respirare e sillibare sapra ben cantare” (translated, “he who knows how to breathe and pronounce well knows how to sing well”).15,16 While the subject of good pronunciation is beyond the scope of this paper, it is easy to understand why good breathing is crucial for good singing. In order to vibrate and generate pitch, the vocal folds require air to move between them. The principal anatomical mechanism by which air enters and leaves the body is the breath. A poor breath will generate pitch less effectively than a good breath. Therefore, one must breathe well to sing well. To learn how to breathe well, one must turn to the anatomy which allows one to breathe.

Air, the oxygen which allows every cell within the body to remove certain waste products, is stored in the lungs upon inhalation, where most of it remains before being released from the body during exhalation. The lungs, however, do not control their own expansion; they have no muscular tissue by which to achieve this. The lungs must therefore rely on other parts of the body to expand for it: the inspiratory muscles. Of the many muscles involved in the process of inhalation, the two primary muscles are the diaphragm and the external intercostals. The diaphragm is a dome-like muscle inside of the ribcage which, when contracted, moves slightly downward at the top of its “dome.” The external intercostals are the muscles on the outside of the ribcage, in between each rib, which, when contracted, move each rib outward, similar to a balloon being inflated.17

These inspiratory muscles, which are connected to the lungs, allow the lungs to expand. Through the principle of Boyle’s Law, which states that gases and liquids from an area of high pressure will want to move toward an area of low pressure if possible until there is no difference in pressure between the two areas, air enters the now expanded lungs. With this basic anatomical understanding, it is appropriate to turn to how one feels their inhalation as they sing.

The Process of Inhalation

Most pedagogues note three different types of breathing: clavicular, abdominal, and costal.18 It is largely agreed that the first of these, clavicular breathing, is the sort of breathing that primarily moves the upper part of the chest, near the shoulders and clavicles. Vennard refers to this sort of breathing as “the kind of breathing used by the exhausted athlete, the person who is ‘out of breath.’ It is the ‘last resort,’ desperate breathing.”19 Singers should treat this sort of breathing as the last resort. The primary issues which come from clavicular are an insufficient breath – the upper lungs have a much lower capacity than the lower lungs – and little control over the exhalation.20 David also notes that such breathing creates tension in the throat – a major issue for singing.21

Abdominal breathing is perhaps the most noticeable of the three breathing types. This type of breathing primarily relies on the action of the diaphragm. When the diaphragm contracts to expand and fill the lungs, this expansion pushes the internal organs beneath it further down. Because there is no room for the internal organs to move directly downward, they instead push against the abdominal wall which moves outward to compensate, leading to the outward appearance of a substantially expanded stomach.22 This expansion is advisable, though difficult for a young singer to achieve. Perhaps this is due to societal expectations of thinness, which the expansion of the stomach goes against directly, discouraging people from expanding the abdomen in a natural way to avoid the appearance of being large. To help singers achieve this expansion, David notes, “a full length mirror and the student’s hands are the best tools available.”23 Students can observe their own breathing visually with the mirror and should notice the expansion of the abdomen as they inhale. The hands may also be placed on the abdomen, one near the navel and the other on the natural waist, to feel the abdomen expand. Students may also observe their abdominal breathing by lying on the ground and inhaling. Vennard recommends supplementing this by placing a moderately heavy object on the abdomen and giving the student the goal of raising the object with each inhale and lowering it with each exhale.24

Of the types of breathing, costal breathing is perhaps the least noticeable, but it is nonetheless highly useful for the singer. David argues for a fourth type of breathing, costal-abdominal, which relies on both costal and abdominal breathing and is the most effective type of breathing for singing.25 Costal breathing relies on the external intercostal muscles. The expansion of the space between the ribs allows for a fuller space into which the lungs can expand, and thus, more air which one can control upon exhalation. This sort of breathing is closely related to abdominal breathing: As David notes, “some rib expansion is inevitable with diaphragm contraction [inhalation from abdominal breathing].” That being said, David notes that further expansion is advisable, saying that one can help their students achieve this by instructing them to fill up an imaginary inner tube in their abdomen at the waist.26

Not all teachers agree that costo-abdominal breathing is the ideal. Many have historically believed “the rib muscles should only be used to expand the ribs and keep them in this position making possible the most efficient operation of lower muscles, the true motors of breathing.”27 There is some validity to this; the majority of the expiratory muscles (discussed in a later section) are beneath the ribs in the abdomen, so they cannot control the air that is gained from costal breathing. If not being able to control the air is one of the primary reasons that clavicular breathing is inadvisable, it stands to reason that costal breathing should be discouraged as well. Unlike clavicular breathing, however, costal breathing does allow for control of exhalation through the interaction between the external and internal intercostals.

One can thus safely follow David’s costo-abdominal breathing without sacrificing singing quality.

Before moving on to the anatomy and process of exhalation, it is important to touch on a few miscellaneous points about inhalation. First, it is important to note that inhalation should be a silent process. Noise during the inspiratory process may be a sign of issues that will seriously affect singing. Most often, a noisy inhalation is a sign of a lowered soft palate, a too-narrow mouth opening, or a partial blocking of the airway by the tongue resting too far back.28 These issues ought to be resolved for a good breath and a good tone.

Second, while the process of inhalation involves a great number of moving parts, the whole process itself should be quick. Singers are often required in repertoire to inhale enough to get through fairly long phrases, in the space of a fraction of a second. Thus, while it is crucial to teach students how to breathe most effectively, it is also important to help them learn to do all this in short lengths of time. The third point makes drawing quick breaths easier, but it is important in isolation as well: one must not inhale too much. As Davids and LaTour note,

Singers should take a full breath because a relatively high lung volume helps to maintain a low larynx position, which in turn may help to reduce mechanical stress on the thyroarytenoids … At the same time, avoid the temptation to take as much breath as possible.29

Particularly when approaching long phrases, it will be the instinct of a young singer to fill the lungs completely in order to get through the full phrase. This is counterproductive. Richard Miller argues that by doing this, the lungs are so full to bursting that it will result in an unavoidably higher rate of exhalation. This means that the singer is less likely to sing through the full phrase than if they had taken a breath that was full, but not over-full.30 Finding this balance will take time, as one is not accustomed to taking deep, full breaths in their everyday life. However, as a singer becomes more familiar with their own voice and body, and as they learn how much breath is needed to sing a phrase of any given length, they will become more accustomed to the feeling of an appropriately full breath.

A good inhalation is important to the process of breathing. Such an inhalation relies both on a good costo-abdominal breath, which expands the abdomen and spreads the ribs. One must not, however, engage in the inefficient and harmful clavicular breath, nor should one inhale noisily. One must take a full breath, but not too full a breath, else they risk a too-rapid exhalation.

The Anatomy of Exhalation

Finally, we arrive at the final component process of breathing. In the typical functioning of the human body, air is exhaled once the cardiovascular system has reached a point of diminishing returns in gathering oxygen from the air in the lungs and replacing it with carbon dioxide. At this point, the expiratory muscles bring the lungs back to the position in which they began inhalation. Because the volume of the lungs is significantly decreased from this process, Boyle’s Law works in the inverse way as it did for inspiration. The air pressure within the lungs becomes much higher than the air pressure of the atmosphere, leading air to escape the lungs to maintain equilibrium between the two areas. The primary muscles used to achieve this action are more numerous than those used in inspiration, though, like inspiration, there are more muscles which are less involved. These muscles are the internal intercostals, the external and internal obliques, the rectus abdominis, and the transverse abdominis. The internal intercostals may be paired with the inspiratory external intercostals. They lie in the same place as the external intercostals, though the fibers of the internal move in the opposite direction than the external. Instead of pulling the ribs apart, as the external intercostals do, the internal intercostals bring them together, collapsing the ribcage.31 The external obliques run from the fifth rib down to the top of the pelvis, with muscle fibers that run the same direction as the external intercostals.32 The internal obliques have a similar relationship with the external obliques as the internal intercostals have with the external intercostals, running mostly perpendicular to their external counterparts. One way in which the two oblique muscle pairs differ is that the internal obliques run from the pelvis only up to the last rib, wrapping from the spine to the side of the abdomen.33 The rectus abdominis is separated into four sets of muscles going from the middle of the rib cage down into the pelvis, reflected across the centerline of the body to make a total of eight. These rectus abdominis muscles are at the very front of the abdomen, with muscle fibers running perpendicular to the floor.34 Finally, the transverse abdominis sits in the front of the body, wrapping around to the sides, and goes from the sternum down to the pelvis, with muscle fibers running almost perpendicular to the rectus abdominis.35 Because the primary expiratory muscles are more numerous than the primary inspiratory muscles, the work done by each individual muscle is less defined. However, as a whole, the muscles contract the abdomen and rib cage in order to return it to the position in which they sat before the inspiration.36 With this understanding of the expiratory anatomy, one may begin to understand the way the expiratory process differs in singing than in normal bodily operation.

The Process of Expiration

When one exhales in typical bodily function,37 the primary goal of exhalation is to evacuate the lungs in a relaxed manner, so when more oxygen is needed, the lungs can fill up in inspiration in the same relaxed manner as is typical (though the relaxedness of this process may be subject to the level of physical exertion). However, when singing, the objective is very different. The breath is the system which propels the vocal folds to make sound, and as such, the breath must be controlled to use it most efficiently. The amount of air required to move the folds efficiently and most effectively is quite small relative to the amount of air expelled at once in typical expiration. As such, one needs a system by which to slow the amount of air leaving the body during singing.

There are a variety of systems to manage exhalation. Miller lists several, including the “down and out” method, which encourages a focus on distending the abdomen outward. One may perhaps equate this to a preference for the action of the inspiratory muscles. There is also the “up and in” method, which encourages bringing the abdomen inward, accelerating the action of the expiratory muscles.38

These systems each have flaws. The “down and out” method places far too much emphasis on the distention of the abdomen. In the process of maintaining this distention, the singer may be encouraged to relax their good posture in favour of the distention, which harms the breathing process as a whole. The “up and in” method encourages a faster expiration than is needed or optimal for good singing. This leads to an aspirate phonation, or a phonation in which too much breath is used. The expiratory system which seems to be most prevalent in the literature is what is known as the appoggio method.

As James Stark notes, the root word of appoggio, “appoggiare,” is an Italian term which means “to lean.” Stark argues that this means two different things: first is the leaning of the breath on the larynx, through which the glottis (a piece of cartilage just above the vocal folds) slows the expulsion of the air.39 There is a limit to the amount of air that can be expelled during the open phase of the vocal fold oscillation. Provided there is a firm closure to begin with, this “leaning” will limit the amount of air leaving the body. The second component of appoggio is the leaning of the expiratory muscles on the inspiratory ones. Stark notes that this is often described as “a feeling of ‘bearing down’ with the diaphragm.”40 Given the complexity and difficulty of feeling the use of a single muscle, it is difficult to scientifically justify the feeling Stark describes. But the point is well understood. Rather than completely release the inspiratory muscles from all activity, the singer must continue to engage these muscles in the process of singing in order to slow the speed of the exhalation. Many authors, including Vennard and Miller, refer to this as “muscular antagonism.” This term, while more narrow than appoggio, is perhaps more descriptive and more useful in explaining the “muscular antagonism” aspect of the historical appoggio. The muscular antagonism is also the element which will conclude this discussion of breathing.

How may one achieve this muscular antagonism? Unsurprisingly, there are a variety of opinions on this subject. No one way to think about this subject is perhaps the “best,” but instead, one may benefit from borrowing from each of them. Vennard offers that one may feel the muscular antagonism as a feeling of “sitting on the breath.”41 Naturally, this must not be taken literally. The breath is not solid enough a thing upon which one can sit. Instead, one may interpret this to mean that one may settle into the sensation of the inspiration. It may help to gain comfort with this sensation by doing as Davids and LaTour suggest and engaging in a brief suspension of the breath.42 The sensation of active inhalation is somewhat different from the sensation of keeping these same muscles activated for muscular antagonism. By suspending the breath, a student may become accustomed to the sensation of maintaining muscular action of the inspiratory muscles during exhalation. This suspension is one of the aspects of the famous Farinelli exercises, in which a singer inhales, holds the breath, then exhales for gradually increasing counts – though Davids and LaTour seem to suggest a suspension much more brief than Farinelli. Davids and LaTour also caution that during such suspension, one must keep an open glottis. If one closes the glottis during this suspension of breath, it may encourage a hard glottal onset and therefore a pressed phonation, which is suboptimal. Miller notes that in order to maintain a good muscular antagonism, one must also maintain a good posture. Specifically, Miller highlights relaxed shoulders and a noble sternum, without which one cannot successfully maintain muscular antagonism.43 This is due to poor posture giving the ribs and abdomen less space to expand, which in turn harms the inspiratory muscles’ ability to fully engage, making it difficult for them to continue staying engaged throughout expiration.

Conclusion

Finally, one has a full picture of the process of breathing for singing. It begins with a good posture, continues through a full, but not over-full, costal-abdominal breath, and ends with an expiration that takes advantage of muscular antagonism to release the air at a controlled rate that is substantially lower than the rate typical of bodily function. With a mechanism so complex as the human body, it is little wonder that there is such a variety of opinions on the subject of breathing – especially in something so unnatural as classical singing. If the pedagogues have taught anything, it is, first and foremost, that Tennyson was wrong in his assessment: There is nothing dull about breathing.