Mormon Settlers

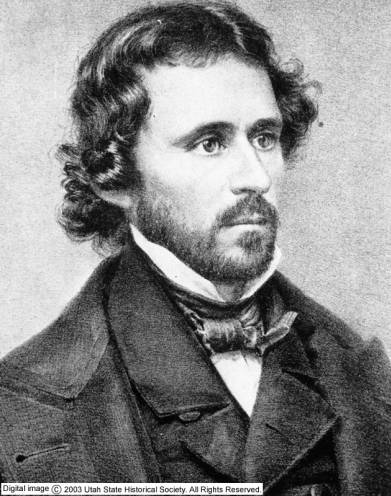

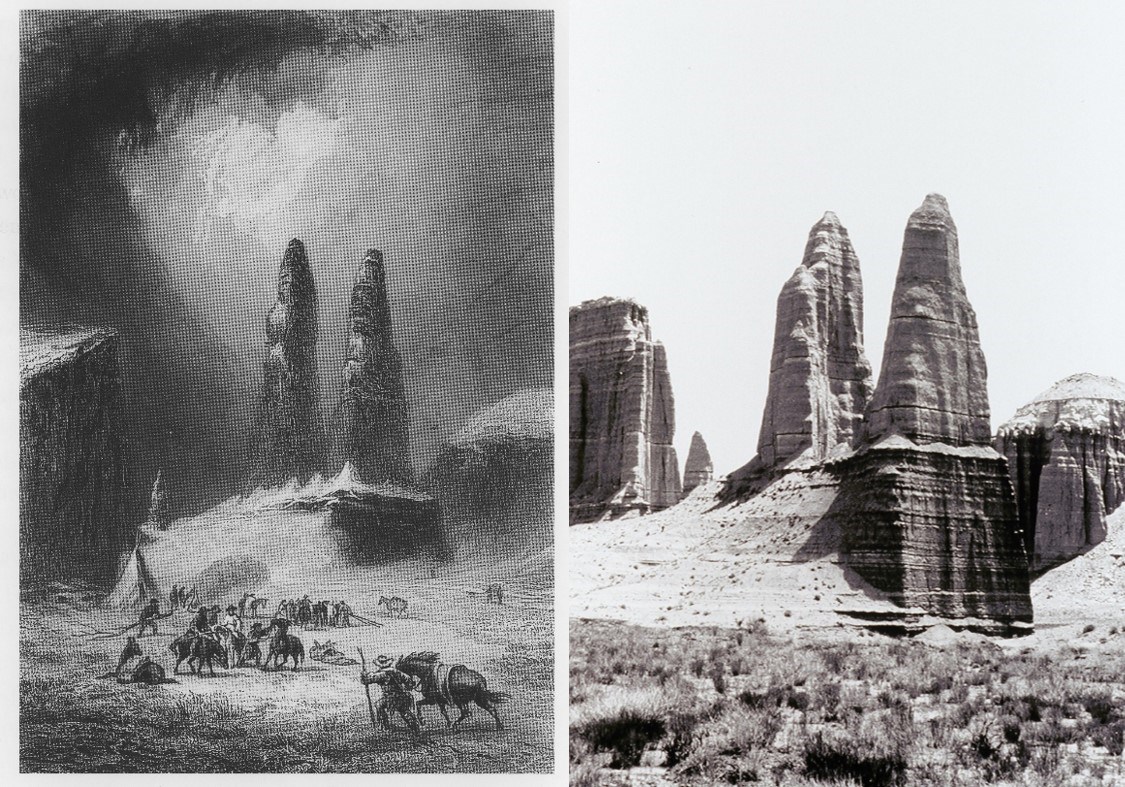

Frémont, wanting to document his journey by every means available, hired Solomon Nunes Carvalho, a daguerreotypist, to do the pictorial documentation of their expedition. Daguerreotype was new and very exacting in its process: a picture was captured by using a mirror-finished sheet of silver-plated copper treated with halogen fumes which made the surface light sensitive; the plate was then exposed in a camera for a few seconds or much longer depending on the lighting of the subject; the exposure left an image on it visible by fuming it with mercury vapor; the plate was then treated to remove the sensitivity to light, rinsed, dried and sealed behind protective glass. Despite the difficulty of the daguerreotype equipment, and the delicate nature of the business, Carvalho managed to take nearly 300 images during their journey. There are only a few of those images left as most were destroyed in a fire. One surviving image shows rock monoliths from the northern area of Capitol Reef now known as “Mom, Pop, and Henry.”

Frémont also encountered various Ute and Southern Paiute Indians in his travels. The expedition, while providing vital information on the region’s terrain, failed in locating a viable route for the railroad. The area proved to be too rugged and difficult to traverse. Additionally, Mormon settlers had been spreading across the Utah Territory for nearly 20 years, yet the entire area around the Reef lacked any real documented exploration.

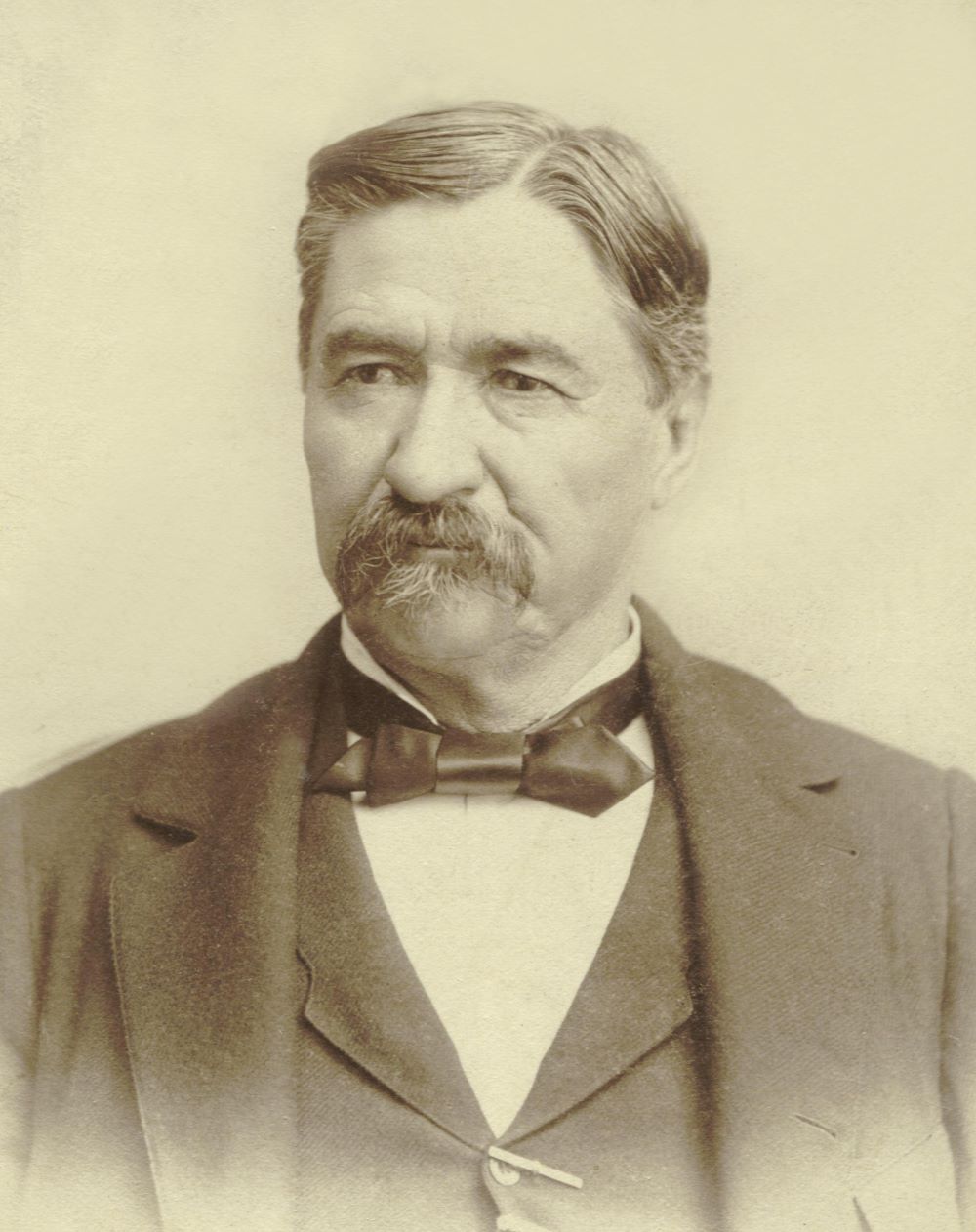

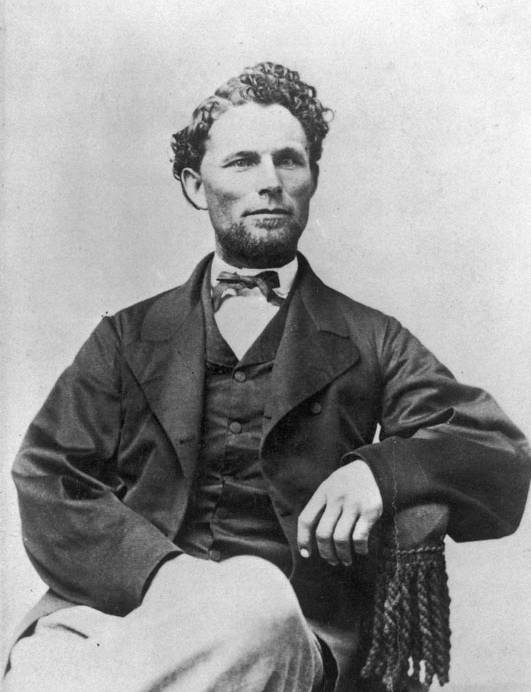

In the fall of 1866, after the killing of some Mormon settlers in the Pipe Springs area on the Utah- Arizona border, a group was organized under the direction of Captain James Andrus to deal with the Indians.

This Mormon Militia was to “chastise” the hostile groups of Indians and appease the others. They were also charged with identifying all potential crossings on the Colorado River to the mouth of the Green River.

Andrus had a company of 62 officers and men who were to travel across the Kaibab Plateau and report on any resources and potential settlement sites. This reconnaissance would provide the first written description of what is now known as the Waterpocket Fold. One officer in particular, Franklin B. Woolley, kept a detailed journal where he wrote:

“Stretching away as far as the Eye can see a naked barren plain of red and white Sandstone crossed in all directions by innumerable gorges.... Occasional high buttes rising above the general level, the country gradually rising up to the ridges marking the 'breakers' or rocky bluffs of the larger streams (sic). The Sun shining down on this vast plain almost dazzled our eyes by the reflection as it was thrown back from the fiery surface...We found no trails leading into nor across this country.” ( C. Gregory Crampton, ed., "Military Reconnaissance in Southern Utah, 1866," Utah Historical Quarterly 32 (Spring 1964) 156-57.)