Tools of the Trade

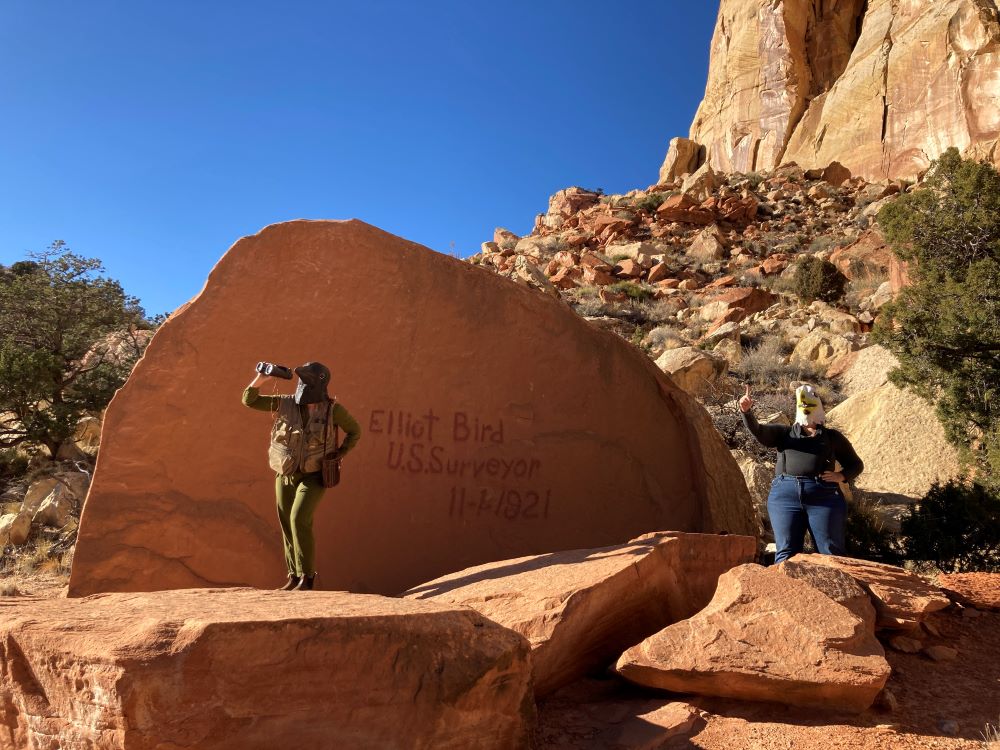

In Bird's 1921 survey report, he detailed his tools of the trade, but might have been

a bit mixed up on the exact type of Transit he used. He called his a “Young & Sons

light Mountain Transit, Model 8531.” Perhaps Young & Sons didn’t make a Light Mountain

Transit, but another company, Gurley did. Survey work couldn’t be done without a Transit,

and William J. Young invented the Transit in 1833 for railroad surveys. Perviously,

people had used the English theodolite which was more expensive, more accurate, and

easy to break.

According to the Smithsonian Museum: The transit was ideally suited for use in the United States. It was efficient: since

the telescope can be reversed end for end, surveyors could take sights forward and

backward along the line. It was rugged: an early commentator noted that a transit

"cannot be made totally useless by any accident short of absolute breakage of the

parts." This ruggedness was especially important for surveyors who were often many

weeks away from any shop that could repair their instruments. And it was economical:

throughout the 19th century, a good transit cost no more than $150 and would last

a lifetime and beyond.

Bird also used a Smith Solar Attachment, although he also wrote that he used Polaris

(the North Star) to make sure everything was lined up. “At my camp … at 4:37 am …

I observe Polaris at a western elongation with the telescope in direct and reverse

positions, and mark the line thus determined with a tack in a stake firmly driven

in the ground … at 8 am I lay off the azimuth of Polaris which is 1 degree 25 feet

to the east, and mark the meridian thus determined with a tack in a stake firmly driven

in the ground. … at 9 am , with the transit in the meridian, I set off 38 degrees

11 feet north on the latitude arc; 15 degrees 13 or 19 feet south on the declination

arc; and determine a meridian with the solar which I find agrees with the true meridian.”

He does another solar test at noon and writes, “I made a meridian observation of the

sun for time and latitude, observing simultaneously the altitude of the sun’s lower

limb and the transit of the sun’s west limb, reversing the telescope and observing

simultaneously, the altitude of the sun’s upper limb and the transit of the sun’s

east limb. … which agrees with the computed declination of the sun.”