As told by Andrew Jensen

They called me the “Ghetto Professor” because I worked tirelessly in the slums of Nigeria. I passionately worked with these young gang members, sharing the story of my brother and sacrificing many hours to ensure that members of my community could get a higher education.

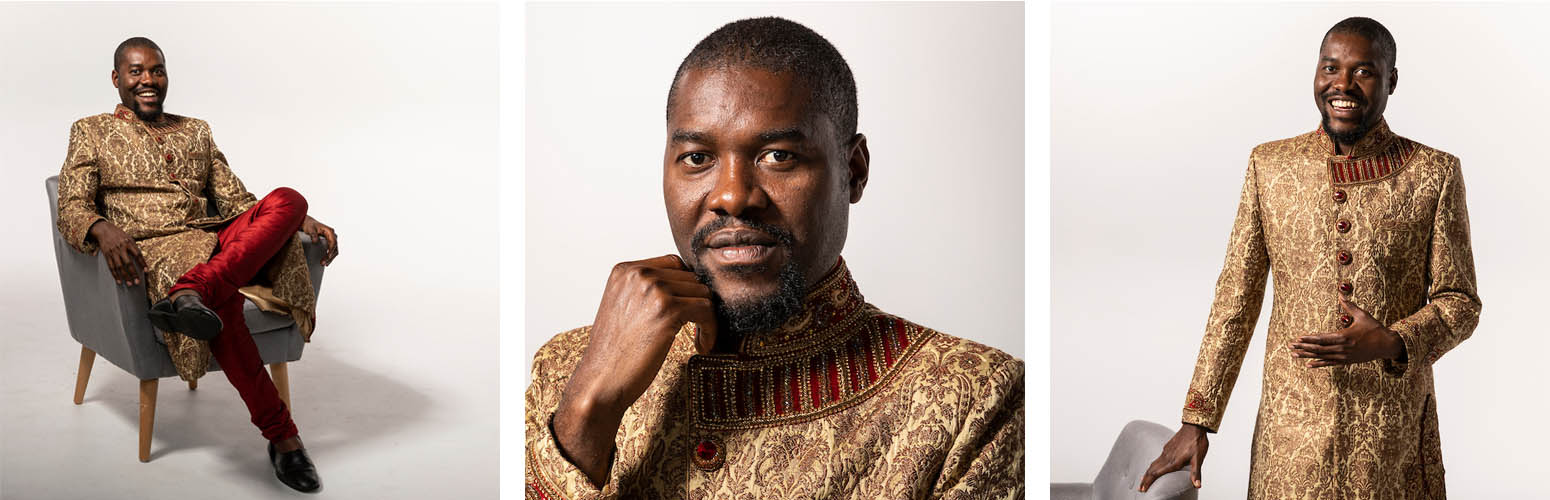

Photo by Gabriel Mayberry

I grew up as a child playing in the slums of Benin City in southern Nigeria. The slums in Nigeria are some of the worst slums in the world. My entire family survived on the Nigerian equivalent of 50 cents per day, meaning that we could only afford one meal per child per day. Early in my life I learned to eat at exactly noon — if I waited too long I didn’t have the energy to do anything, and if I ate too early then I would be even hungrier the next day.

Realizing how poor my family was, at 8 years old I began working selling newspapers. On my first day of work, I thought I was the smartest kid in the city because I decided to head to the market square in Benin City. Little did I know, many people had the exact same idea as me. To set myself apart from the crowd, I learned how to balance the stack of newspapers on my head while playing a drum, singing, and dancing to advertise my goods. This was my reality throughout my childhood, working to support my family where I could. To attend school in Nigeria was around $20 per month, meaning as a young child I wasn’t able to attend school with kids in my age group, so I eventually dropped out.

When I was 13, I started a new construction job that paid better and allowed me to save and attend school. I did not, however, have the money to take the bus because every coin I had went to supporting my family and school fees. This meant that every day I would work, walk 5.3 miles to school, and then walk 5.3 miles back home at the end of the day. This cycle — work, walk, school, walk, home — continued for many years. I persevered and completed my high school education, now confronted with the reality of trying to attend college. In Nigeria many educated adults are unemployed, so not many people believe in the importance of higher education. Many gangs in Nigeria use this challenging circumstance to recruit youth during their school days with the promise of basic needs like food and a better future, convincing them that they don’t need an education. One of my closest cousins, who I have always called my brother, was one of the people recruited into the gangs and was killed during an encounter with another gang. It was hard to hear that my closest brother had been robbed of his life, so I decided to do something to fight back against the gangs. I was tired of watching my community have their education held hostage by these people.

I decided to start a program called “Remedial Education,” a free educational program designed to help youth and adults pass the Nigeria equivalent of the GED (called GCE) and get into college. I would recruit people from the community, specifically targeting young members in the gang. I knew that I could convince them to try to get an education instead of working with the gang. They called me the “Ghetto Professor” because I worked tirelessly in the slums of Nigeria. I passionately worked with these young gang members, sharing the story of my brother and sacrificing many hours to ensure that members of my community could get a higher education. This made several of the prominent gangs unhappy, leading to a confrontation between myself and a few members of a violent gang. They held a gun to my head and told me that unless I stopped recruiting kids for my school program, they would kill me. They fired a gunshot right next to my ear, which caused massive pain and a week of deafness. I was absolutely terrified. I knew from this point that getting an education in Nigeria would be too difficult for me.

I had heard about a wealthy philanthropist that was visiting Nigeria and wanted to give out a few scholarships to attend school in America. I found information about his program as I was trying to get help for students willing to go to college but couldn’t afford it. I applied with the dream of going to America for my education. I arrived at the testing center where they would decide the scholarship recipients and was immediately overwhelmed by the thousands of people there to compete for only 50 scholarships. I took the tests and went home completely uncertain but content, knowing that I had given it my best shot. A few days later, some of my students came to me and said, “Ghetto Professor, Ghetto Professor, you made it — you made it to America!” I laughed, thinking that they were teasing me again and didn’t think anything of it. A few hours after that, one of the adults in my town came running to me and confirmed I had actually won one of the scholarships!

Just like that, I began my search for a college in the United States. I already had specific criteria in mind, I was looking for a school that had a diverse student body and a strong inclusion program that I would be able to be a part of. Upon a few Google searches, I narrowed the choices down to a school in California and Utah Valley University. Upon reading the information about tuition, I called the international office at UVU and immediately felt that Utah Valley University was the place for me.

When I arrived at the university, I found it was exactly as it described online. It was a diverse campus that allowed me to get involved and be included at every chance I got. I was able to participate in an engaged-learning course where we traveled to Salt Lake City to work with people that were homeless. I immensely enjoyed my time while I was at Utah Valley University. Everywhere I turned there were supportive faculty, staff, and students that helped me to realize my dreams for an American education.

Several years after starting UVU I returned to my home in Nigeria, no longer the scared boy that ran away from the gangs. I was ready to share everything I had learned with my community. Upon my return, I was received with great celebration. I was shocked by the number of people who came to welcome and talk with me about my experience. I asked my uncle why so many people were coming, and he told me that I had changed the narrative of hopeless life in the ghetto. I was able to help them see that education is the key to open doors, to reach greater heights, and to realize my full potential.

For days, youth and adults would come by my house to ask about my American education, the American people, the culture, food, and lifestyle in America. I told them everything I know about America, and — most importantly — I told them about UVU and what the school meant to me. I told them about the university’s mission, values, and programs. In my home of Benin City, Nigeria, there are groups of young students studying diligently with the intent to attend UVU someday. I’m so proud to call Utah Valley University my home.